The Civil War in 1,000 Words

Dan Bryan, March 10 2012

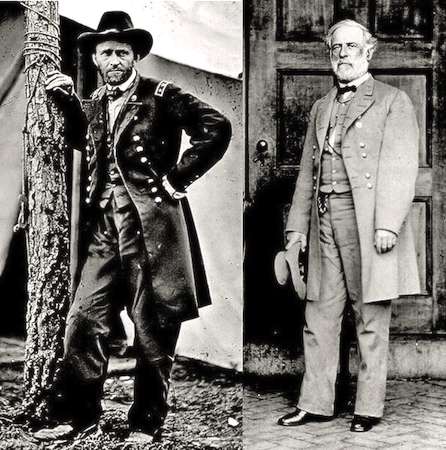

Ulysses Grant and Robert E. Lee.

Ulysses Grant and Robert E. Lee.Causes of the Civil War

There are many other "causes" of the Civil War mentioned beyond that of slavery, but the main cause of the Civil War was slavery. The southern states seceded specifically to defend this institution.

Without the specter of abolition haunting the south, none of the other "causes" would have been nearly important enough to warrant succession.

The first shots

When Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860, southern indignation was immediate. Several states had threatened to secede if he won, and they soon began carrying out that threat. South Carolina was the first state to do so on December 20, 1860. Other states in the south soon followed, and they called themselves the Confederate States of America.

The Civil War began with a confederate takeover of Fort Sumter, which was in South Carolina but still manned by US troops. The date was April 12, 1861.

Both countries began raising armies in haste after this engagement.

Military tactics

The Civil War is widely considered to be a military tactician's dream. Rifles were much more accurate and faster loading than they had been in the age of Napoleon. The largest armies consisted of over 100,000 men. Artillery, cavalry, and naval forces all played a crucial role. The type of battles ranged from the shock attacks at Chancellorsville to the long sieges and trench warfare of Vicksburg and Petersburg.

It was probably of little consolation to the 620,000 troops who died, but they were participating in campaigns that aficionados marvel at to this day.

1861: The first battles

Both sides tried the simplest strategy first. The Union raised an army in Washington and marched it towards Richmond. The Confederates raised an army and encamped it halfway between the two cities. The two armies met and shot at each other until the Union troops turned and fled. This was the first battle of Manassas.

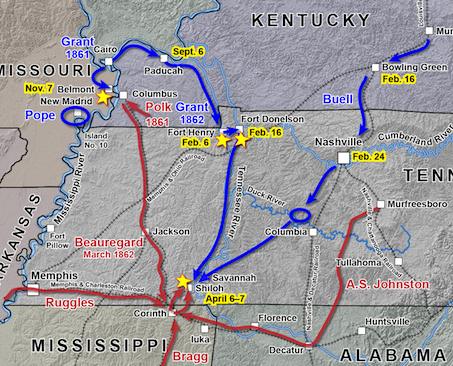

In the meantime the Union had better luck advancing down the Mississippi River, and in securing the border states of Missouri and Kentucky.

1862: Momentum for the south

The Union put George McClellan in charge of the main army. He conceived of a bizarre plan to land it amphibiously on the Virginia shore and to march on Richmond from the east. This even though the city was a mere 100 miles from Washington via the overland route.

McClellan got his army within a few miles of Richmond, but was defeated in battle by Robert E. Lee and turned back. McClellan became known as cautious to his own detriment.

While McClellan was retreating back to the coast and sailing his army up the Chesapeake to Washington, Robert E. Lee decided to mount an invasion of Maryland. McClellan met Lee at Antietam on September 17. Even though the Union had twice as many troops, McClellan was unable to deliver a decisive victory in the bloodiest day of the Civil War. However, Lee was forced to retreat his army back to Virginia.

Meanwhile, in the west, a general named Ulysses Grant was steadily advancing southward, cutting through most of Tennessee. The Confederates tried and failed to push his army back at the battle of Shiloh. By the end of the year, Memphis and New Orleans were occupied, and Vicksburg was the Confederates' only foothold on the Mississippi River.

1863: Smashing victories for the Union

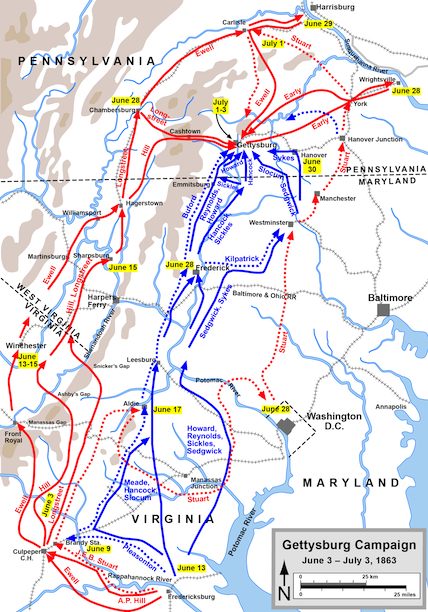

The Confederates continued to win battles in the east. After outmaneuvering the Union in a series of battles, culminating with a win at Chancellorsville, they embarked on a second invasion of the north. This time they made it through Maryland and into Pennsylvania, foraging off of the land as they went.

Gettysburg was a key road junction and Lee tried to unite his army there. The Union army had the exact same idea and the biggest battle of the war ensued. On the third day, the Confederates attempted a full frontal assault and were decimated. After a long retreat to Virginia they now found themselves so heavily outnumbered that there was no room for offensive action.

In the mean time, the Union under General Grant took Vicksburg in July 4th, severing the Confederacy in two and ending combat action on the far western front. Most of the Union forces spent the ensuing months repositioning themselves to eastern Tennessee, with an eye towards striking into Georgia.

1864: Stalemate and attrition

After several other Union generals had failed to counter Lee's aggression, Abraham Lincoln appointed General Grant to command the main army in Washington. Grant's strategy was to make use of his superior numbers and relentlessly attack the Confederates, until their army broke under the pressure. He also hoped to surround them completely, but he never was successful. After taking 65,000 casualties in seven weeks, however, the Union was able to box the Confederate army in at Petersburg, and a long siege ensued. The Confederates were unable to retreat any further because the last railroad line into Richmond passed through that town.

In eastern Tennessee the two sides sparred for months, before the Union under William Sherman attained the upper hand. Eventually they were able to move into Georgia and, after some vicious battles, they occupied Atlanta and had the Confederate Army broken.

Confederate general John Bell Hood attempted to attack Tennessee, with the goal of using his army to divert Sherman's much larger army. However, the Union had so many troops that they were able to stop Hood and march through Georgia at the same time.

By the end of the year Sherman's army was moving into South Carolina, almost unopposed.

1865: The final victory

In the meantime, the "siege" at Petersburg continued (in reality, Lee was only surrounded on two-and-a-half to three sides. However, he could not retreat without sacrificing Richmond). The two sides dug into trenches which bore similarity to the trenches later seen in World War I. Aware of their massive material advantage, the Union army kept stretching the lines out further and further, making the Confederate defense increasingly thin. There were numerous battles and many men killed, but no decisive breakthroughs.

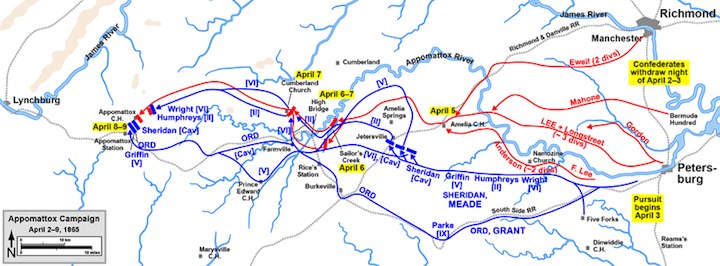

Finally on April 1, 1865, Lee was forced to retreat. Nine months of battle had fatally weakened his army, and staying in place would only ensure its destruction. His last hope was to retreat from Petersburg and Richmond to the west, then turn south into North Carolina and coordinate with remaining Confederate troops there, under Joe Johnston. Had everything gone perfectly, those two armies combined would be as large as Sherman's army, and they might have a brief window of opportunity to attack and defeat that army before Grant's army could join the action (or vice versa, if they fought Grant first).

The plan was a long shot, but to remain in Petersburg any longer meant certain defeat. So Lee marched, but Grant could see the plan clearly, and was more than able to contain Lee's army. On April 9, Lee was finally surrounded at Appomattox Court House, and the famous surrender took place at that location.

Aftermath of the Civil War

Less than one week after Lee's surrender, Abraham Lincoln was killed. This complicated the readmission of the rebellious states, but it did not prevent the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. Slavery in the United States was ended and the nation was reunited.

The period of time after the Civil War was known as Reconstruction.

Recommendations/Sources

- Shelby Foote - The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 1: Fort Sumter to Perryville (Vintage Civil War Library)

- Bruce Catton - This Hallowed Ground: A History of the Civil War (Vintage Civil War Library)

- Ulysses Grant - Ulysses S. Grant : Memoirs and Selected Letters : Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant / Selected Letters, 1839-1865 (Library of America)