The Great Mistake - Why Did the South Secede in 1860?

Dan Bryan, January 27 2013

The Civil War was by far the most catastrophic event to ever happen in the American South. There have been at least a few discussions on whether Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans should have prosecuted the Civil War, but surprisingly very little analysis on whether South Carolina's secession in 1860 was a strategically wise move in the context of the American debate on slavery and states' rights.

Secession was driven by the Southern planter class. For the purposes of this article, let's stipulate that the preservation of slavery and the plantation economy was the primary objective in seceding from the United States. If that was the point of secession, then the strategy was an obvious disaster.

In that case, this essay aims to examine two things:

- What would have happened had South Carolina (and the other Confederate states thereafter) not seceded after Lincoln's election in 1860?

- Would these scenarios have represented an improvement (for the elite planter class) over the devastation of the Civil War, followed by the total abolition of slavery?

It is the contention here that secession was an utter disaster for the South. Because of that the people responsible for it presented the issue later as a question of whether the Union should have intervened and fought the Civil War -- avoiding the question of whether secession was wise in the first place.

The Election of 1860

The proximate cause of the South's secession was the election of Abraham Lincoln with a Republican majority in 1860. However, in and of itself, secession was a major overreaction to this political setback.

Lincoln's election fed the perception that Southern interests were losing control of the federal government, and that this government would eventually suppress the institution of slavery or outlaw it altogether. However, Lincoln's victory in 1860 was far from dominant. As the Republican candidate, he received 1,887 votes in Virginia and did not appear on the ballot in any other state which eventually joined the Confederacy. At the same time, he won other states (such as California, Oregon, Illinois, and Indiana) by somewhat narrow margins. Only in the Upper Midwest and in New England did he have a dominant political position.

Southern extremism on the slavery issue had split the Democratic Party into three factions who were unable to effectively compete with the Republicans. Had the Southern states seated their Congressional delegations after 1860, the Democrats would have operated as a minority, but not overwhelmingly so. In the Senate things would have been very close to deadlocked -- with a possible Democratic majority.1

In other words, secession in 1860 was an extremely preemptive move for the Confederate states to take. There was no immediate proposal to abolish slavery, the Democrats still had enough political muscle to obstruct such attempts, and there was still a large faction of the North that opposed taking any drastic action on slavery. If the movie Lincoln has shown the difficulties of passing the 13th Amendment in 1865, after four years of insurrection, it is very hard to imagine the same legislation passing with a full Southern contingent in Congress, going through the motions of the democratic process.

1 - Enough Southern states failed to seat their Representatives that we don't know what the precise balance would have been. See the 37th Congress distribution, which does not include most of the South. See also the 1860 Presidential Election results.Why Did the South Secede?

If secession was preemptive and hotheaded given the facts on the ground, why then did the South undertake this course?

Since South Carolina was the catalyst, we will start there. The Secession Convention of that state produced a document entitled, "Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union".

The Declaration asserted that the Northern states had combined in league to subvert the original scope of the Constitution -- namely that:

- the Northern states were failing to return fugitive slaves, in violation of their obligations under Article Four of the Constitution.

- the Northern states tolerated abolitionists and insurrectionists (such as John Brown) who incited slaves in the South to rebel.

- misguided political and religious beliefs in the North made future sectional unity impossible.

- some states were elevating persons "incapable of becoming citizens" (i.e. free blacks) and using their votes to support anti-slavery policies.

- the Republican Party was planning to wage a war against slavery upon taking office in March 1861.

Were these valid fears for the people of South Carolina?

It is true that the Republican Party was united in opposing any further extension of slavery. That is, the Republican Party supported a free Kansas and refused to countenance the idea of admitting another slave state after 1860. It is also true that an abolitionist wing of the Republicans did support an immediate end to slavery. However, abolitionists were not dominant in the Party as of 1860 -- it would take four years of Civil War to win many of the moderates over to the cause of the 13th Amendment.

In short, in spite of the heated rhetoric from Southern planters, there was no indication that Lincoln's inauguration was due to be followed by a swift abolition effort. Now perhaps in the long-term there was a very real danger of the Southern fears coming to fruition, but as of December 20, 1860 there was no Amendment in process to abolish slavery. There was no open talk from Abraham Lincoln that he planned to pursue one upon becoming President. There was no army being mobilized to wage an impending war on the South. If the reason for seceding was to protect slavery from abolition -- then perhaps a better strategy would have been to wait until such an attempt was actually made. Surely at the very least this might have made the Southern cause more sympathetic under the sensibilities of the time.

Instead a faction of radical secessionists called "fire-eaters" manipulated this situation towards their end of leaving the Union. They did so playing on fears of a slave insurrection and the other points listed above, but by winning the political debate they triggered a premature and irrevocable decision. For the Southern elite, seceding in December 1860 was akin to a football team walking off of the field because they were behind 10-3 in the second quarter.

What Would Have Happened Without Secession?

Speculating on alternative history is always problematic, but I believe that it's useful in this case for the purposes of showing just how bad of an idea secession really was for the South in 1860. Below are four scenarios that might have occurred had South Carolina (and by extension the rest of the eventual Confederacy) held tight after Lincoln's election and not withdrawn from the Union.

At a high level the alternatives I outline are as follows:

- The Democrats regain control of the federal government in 1864 or 1868.

- A substantial slave insurrection takes hold somewhere in the Deep South.

- The Republicans propose an abolition amendment at some point after 1860, but while the nation is still united.

- Slavery survives until cotton becomes an untenable cash crop, around 1910.

Now let us examine these in more detail.

1. The Democrats regain control of the federal government in 1864 or 1868.

Most of Lincoln's agenda would have been thwarted with a strong Democratic opposition. It is unclear whether he could have forced a resolution on the end of slavery in the Western territories. Federal support of the First Transcontinental Railroad would have been obstructed, slowing the development of the West. The increase in tariffs that assisted Northern manufacturers would also not have been possible. Finally, it's unlikely that any progress towards the abolition of slavery would have been made in the 1860s.

Faced with these problems it's conceivable that the Republicans could have been the Party to split into two factions in 1864-1868, strange as that idea may sound. There were two very distinct groups within the Party during this era.

- A moderate wing which was mostly concerned with protectionism, a transcontinental railroad, homesteading, and industrial issues. This group wanted the West to be free so that they (and not the Southern planters) could prosper from it. Ending slavery in the South itself was not a great concern. Lincoln was more from this wing of the party as of 1860.

- An abolitionist wing which (obviously) placed the greatest emphasis on ending slavery. While this group also shared many of the economic concerns, they were driven at heart by abolitionism.

It's conceivable, not inevitable, that the moderate wing would have been willing to compromise on slavery to win a victory on tariffs, Western lands, and/or the railroads. Perhaps some legal arrangement would have been worked out granting the South more autonomy within the U.S., with freedom to set their own tariffs and slavery policy. At the first sign of such overtures, the abolitionists might have withdrawn from the Republicans and formed a new Liberty Party. All of this is speculation, but there is no guarantee that the Republican coalition would have remained stable through the 1860s.2

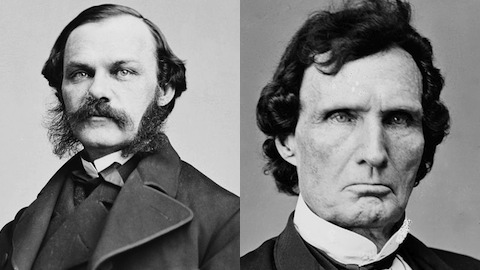

Henry Jarvis Raymond and Thaddeus Stevens were on different wings of the Republican Party

Henry Jarvis Raymond and Thaddeus Stevens were on different wings of the Republican PartyAdditionally, after the disaster of 1860 the Democrats might have been more inclined to run as a national party in 1864 or 1868. Perhaps Stephen A. Douglas would not have caught typhoid in 1861 and instead been the standard-bearer. A Democratic victory in either of those elections would have chastened the abolitionist wing for at least a few years, and the slavery issue might have been suppressed in national conversation until the late 1870s or 1880s. Scenario #3 below will examine this "alternative" late 19th century in more detail.

2 - In fact this very split eventually developed within the Republican Party over the failures of Reconstruction. The business/industrial wing of the Party wanted to compromise on Reconstruction and focus on supporting America's industries and railroads. The radical wing (descendants of the abolitionists) wanted to keep the focus on civil rights for the freedmen. Eventually the radicals were defeated.

2. A substantial slave insurrection takes hold somewhere in the Deep South.

This was without a doubt the nightmare scenario for the planter class, and one that was brought to the forefront by John Brown's abortive coup in 1859.

There are two broad scenarios for a slave rebellion:

- A rebellion fomented by militant Northern abolitionists, potentially much more organized than Brown's flimsy effort.

- A rebellion started and driven entirely by the slaves themselves, or at most with assistance from free Southern blacks. The most obvious (successful) corollary would be the 1790s rebellion in Haiti that was led by Toussaint L'Ouverture.

Southerners had prevented large-scale rebellion for over two centuries, using timeless carrot-and-stick methods of pacifying the slave communities. Productive, non-rebellious slaves could attain positions in skilled trades or as house slaves, where their status (in the eyes of white society at least) and living conditions were somewhat improved. Those who fell out of line were beaten mercilessly and put on the worst jobs thereafter, and obviously those who attempted open rebellion (such as Nat Turner or Gabriel Prosser) were executed. All of the slaves were monitored with constant surveillance from whites and other slaves alike.

The surface nature of this arrangement has even led some observers to make the argument that slaves in the South were not poorly treated as a whole. There is an element of truth to that argument, insofar as slaves who cooperated with the system lived in a modicum of comfort, and insofar as they were much better off than slaves in the Caribbean and even some free whites. This argument however, for rhetorical reasons, entirely ignores the backdrop of violence that held the slave system together. There is no obvious answer to the question of whether tens or hundreds of thousands of slaves might have been killed had a full-scale revolt actually broken out, as I will now examine.

It's very hard to speculate on how the federal government might have intervened had a serious slave rebellion taken hold in the 1860s or 70s. While the seizure of a federal arsenal in John Brown's case made the intervention easy, would the same reaction have happened if 1,000 slaves rebelled? 10,000? 50,000? Would there have been a Democratic or a Republican President at the time of the revolt? Would the broader part of the Republican Party have supported the use of the U.S. military to suppress (and likely kill) such a number of people? Or would the suppression have taken place solely with Southern militias, and would they have been able to stop a revolt once it reached that kind of magnitude?

The event of a mass slave rebellion in and of itself might have been the kind of catalyst for end to slavery -- perhaps one that would have proceeded in a very different manner from what actually transpired. If slaves took over a significant area of land, would they have been willing to turn it over to the U.S.? Would the U.S. military have taken it back by force, with an understanding that slavery would end thereafter? Would the slaves have remained independent like those of Haiti? Would they have been deported en masse to Liberia as some free blacks had earlier been?

From the perspective of the Southern planters, it's hard to tell what would have happened in this scenario, but it is possible that the end result would have been far worse for them than the sharecropping system that eventually developed after the Civil War. However, it's unfortunately more likely that they would have suppressed a large scale rebellion with massive loss of life to the blacks involved -- followed by who knows what.

3. The Republicans propose an abolition amendment at some point after 1860, but while the nation is still united.

Brazil was the last nation in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery, doing so in 1888. Certainly by that point in time the institution of slavery would have been seen in the North as a national embarrassment -- as no less than a moral stain on the flag of the United States.

One tactic to be potentially used by the Republicans would have been the creation of smaller states in the West to drive up the number of sympathetic legislators in Congress. By around 1880 or 1890 they could have created a very strong majority using these tactics and potentially pressed through an abolition amendment. It is also somewhat likely that Delaware and Maryland would have eventually seen themselves aligned with the Northern antislavery coalition.

Without the intransigence of the South in 1860, there may still have been enough voices for compromise to ensure a more orderly system of emancipation. Would an arrangement have been on the table involving financial compensation to the slaveowners? This idea was rejected in the 1850s and 60s, to what limited extent it was pursued. Perhaps by the 1880s or 90s the more prescient of the planters would have seen a decline to the cotton ecology beginning, and would have been willing to "sell high" on the institution of slavery before it collapsed on them.

Of course, there is always the chance that the Civil War would have simply happened at this point in the 1880s, much as it actually happened in the 1860s. The South would have been further behind in terms of industrialization and firepower than they were in 1861, but perhaps they would have accepted this from the start and pursued a strategy of guerilla war. Or perhaps the defeat of the South would have happened much more quickly in this scenario, without the attendant scars to the economy and the Southern psyche that were actually in place by 1865. Finally, there is a chance that changes to the political environment would have enabled an orderly split into the United States and the Confederate States. I don't think that is likely, but we know for sure that it didn't happen when the South seceded unprovoked in 1860.

Under any of these scenarios, a war like that from 1861-1865 killing 600,000 people and devastating the South seems beyond the worst-case scenario.

4. Slavery survives until cotton becomes an untenable cash crop, around 1910.

Slavery as an economic institution was not on the ropes in 1860 -- on the other hand it was wildly profitable. Southern plantation owners were likely the richest men in the world. Cotton remained a highly in-demand crop in the North and in Great Britain.3 There is no reason to suspect that this would have changed in the immediate years after 1860.

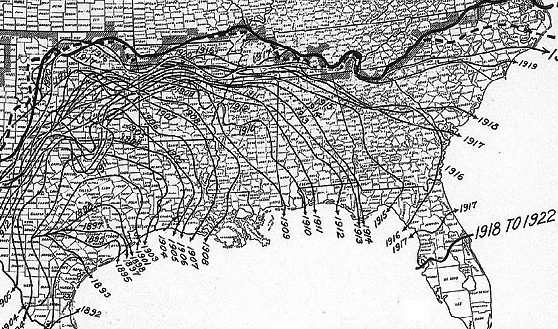

Let us now imagine that slavery has survived all the way through to the turn of the century, navigating the dangers outlined in sections #1-3 above. It is likely that it's death knell would have finally occurred around that point due to the decline of the cotton economy itself.

Cotton as the predominant cash crop of the South survived until ecological issues rendered it untenable on a large scale. These issues were soil depletion and the boll weevil infestation, the latter of which was devastating to the Southern economy when it occurred in actuality (starting in Texas in the 1890s and spreading east from there). Had it occurred in the context of a slave economy, the financial damage would likely have been even worse. While the effects were uneven, and recovery was possible after a few years, it is likely that the attack of the boll weevils would have bankrupted any plantation owner who lived on the edge of their credit line.

First of all, the human wealth represented by the slaves was vast -- almost $4 billion as of 1860 -- and would have only grown by the end of the 19th century. An asset value of this number was supported by the current and potential work that these slaves could perform, largely in support of cotton. A collapse in cotton production would surely have led to a collapse in slave values and land values, dealing a double-blow to the plantation class and probably leading to a calamity in the financial system.

When tobacco began to deplete the soil and become less profitable in Virginia and Maryland (around the 1820s and 30s), many plantation owners sold their slaves to the Deep South to support the cotton industry. By 1910, however, the southern planters would have had nowhere else to sell their slaves to, and would have been anchored to their declining value. It's not entirely clear what else the slaves could have done at this point to warrant the expense of their upkeep to indebted and bankrupt owners. Thus, this scenario is somewhat close to the one actually envisioned by Abraham Lincoln as of the late 1850s, in which slavery would slowly wither in the South as it was cordoned off.

The boll weevil attacks are just one hypothesis for how this system would have become obsolete. Since slavery tied the entire Southern economy to a very specific form of agriculture and away from industrial development, the system lacked the flexibility and adaptability of a true free market economy. Thus it's also possible that the economics of slavery would have collapsed in a different manner, perhaps quite suddenly.

From the standpoint of the planter class in 1860, this economic/ecological catastrophe was an uncontrollable inevitability with or without the Civil War. By not seceding they would have, in this scenario, bought themselves an additional few decades of the slave system with all of the profits which that would have entailed.

3 - As an aside, it's possible that when Britain developed its cotton resources well enough in Egypt and India that it would have twisted the South's arm into giving up slavery (abolitionist society liberals were not unique to the Northern United States). Now is not the space to examine that in detail, but it shouldn't be discarded as a possibility.

Conclusion: Alternate vs. Actual History from 1860 onward

Intuitively, given the passions surrounding the issue by 1860, I'm skeptical that slavery could have survived to 1900 even without the Civil War. I believe that the most likely scenario from above is #1, combined with #3. From the point of view of the Southern slaveholders though, any of the scenarios above would have been an improvement over what happened in the Civil War, with the arguable exception of #2.

By seceding in 1860, without a clear effort in flight to abolish slavery, the South not only jumped the gun but it ensured that support for the Union in the North would be quite strong. Even moderates and Democrats had little choice but to conclude that the South triggered the Civil War (especially after Fort Sumter). This might have been different had the Civil War been seen as something that was imposed by Republican overreach.

In any case, I have used the four hypotheticals above to reiterate the point that secession was a gross strategic error. Given the colossal failure of the Civil War it seems misguided that the debate about it focuses so heavily on whether Lincoln should have intervened, as opposed to whether South Carolina should have seceded in the first place.

Recommendations/Sources

- Economic History - Slavery in the United States

- Alternate History Forum on the South not seceding in 1860

- The Election of 1860

- Cotton and the Civil War

- The Boll Weevil

- Steven A. Channing - Crisis of Fear: Secession in South Carolina (Norton Library, N730)

- Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene Genovese - The Mind of the Master Class: History and Faith in the Southern Slaveholders' Worldview