The Antebellum Home and Woman's Culture (Part 2)

Dan Bryan, March 22 2012

"In America the independence of woman is irrecoverably lost in the bonds of matrimony. If an unmarried woman is less constrained there than elsewhere, a wife is subjected to stricter obligations. The former makes her father's house an abode of freedom and of pleasure; the latter lives in the home of her husband as if it were a cloister." - Alexis de Tocqueville

**This is Part 2 of a two part series. The first article covers the expansion and domestication of the American home in the 19th century.**

As an increasing number of women were liberated from the toil of subsistence farming, and as the American home became larger and more domesticated, there came a need to redefine the role of women in a way that would uphold the domestic order and the proper relation of woman to man.

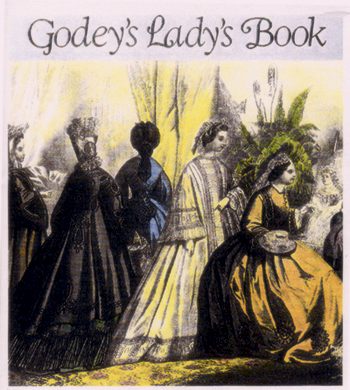

It was in this era that lengthy works on housekeeping emerged like Catharine Beecher's A Treatise on Domestic Economy. At the same time, Sarah Josepha Hale became the editor of Godey's Lady's Book and made it the most popular magazine in the United States during the antebellum times.

Along with innumerable works of less renown, these advocated an expanded appreciation for woman's role within the home, while reinforcing the limits on her adventures into the public sphere. Scholars have termed this ideal Separate Spheres, Republican Motherhood or the Cult of True Womanhood, although these terms were not in wide currency during the 1800s.

Women and education: learning for the sake of the republic

In line with the republican ideals of a new nation, women were encouraged to read, and those of means were fairly well educated as girls. Besides a general appreciation of education, the argument for this practice was two-fold.

First, in an era when romantic love was replacing commercial considerations, it was considered important that a woman have the means to discern correctly between multiple suitors. It was also thought that a woman with charm and personality, and perhaps a touch of wit, would be more interesting to a man both in courtship and in matrimony.

Secondly, women had the responsibility of molding the character of the forthcoming generations. If they failed in that regard, the fragile experiment of an American republic would be doomed to the whims of a base, ignorant rabble.

Politically and economically women remained subordinate. They had no right to vote, no right to own or inherit property if married, and were themselves considered property of their husbands in many respects. Thus, the exalted role that was advocated only applied to a very narrow realm of of living.

Catharine Beecher -- advocate for education and domestic economy

"Woman's great mission is to train immature, weak, and ignorant creatures to obey the laws of God; the physical, the intellectual, the social, and the moral."

Catharine Beecher came from a prominent family of preachers and intellectuals. Her father was Lyman Beecher, and her sister was Harriet Beecher Stowe. Catharine Beecher was a prolific author and advocate on education and women's roles. In an era when teaching was of poor quality in most of the country, she helped direct women into this profession, framing it as a spiritual calling.

Her Treatise on Domestic Economy made her famous. Her advice in this book mixed between the practical and the moral. Parts of it were dedicated to cooking, making clothes, etiquette, first aid, the importance of being an early riser, and so on.

Other times, Beecher became expansive and philosophical. She argued that women had an indispensable role in the defense of American democracy and character. It was their role to instill morals, ethics, and education in their children, and as such they were the true guardians of culture.

This was different from an advocacy of political equality, which Beecher opposed. She believed that the evils of politics would taint the soul of women, and compromise their abilities in teaching and housekeeping. On this basis she opposed the nascent women's suffrage movement.

The notes for one of her chapters in the table of contents sums this point up rather succinctly:

"Question of the Equality of the Sexes, frivolous and useless"

Beecher's book was reprinted many times over, and it was widely read and very influential.

A magazine of some renown: Godey's Lady's Book

By circulation, Godey's Lady's Book was the most popular magazine in the United States in the 1840s and 50s. By the latter decade, about 150,000 households subscribed, and most of the readers were women.

The subject matter of this book was varied. Each issue had hand-tinted fashion plates, and illustrations with sewing patterns for a garment. The content itself consisted of short fiction, editorials, sheet music, and journalistic accounts of events in the United States and elsewhere. In general, the magazine avoided political or controversial issues.

As editor of the magazine, Sarah Josepha Hale was another powerful voice in the conversation about the role and importance of women. She also focused on education, charity, and responsibility, while avoiding most political issues.

While she did express some support for women's employment and their efforts in higher education, she wrote of their role in the household first and foremost. Godey's Lady's Book can be broadly construed of fit within the framework of "Republican Motherhood" or other terms that academics use to describe women's roles in the antebellum period.

An unspoken marriage strike?

There were a small number of women who advocated for equality and political rights, and their story is a long one in its own right. The most famous of them were Fanny Wright, Margaret Fuller, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. However, it is safe to say that their immediate influence was limited.

More numerous were the women who simply chose not to marry. For if the difference between the wife and the unmarried woman were so severe, did it not make sense for the independent-minded to pass upon marriage altogether?

In the northeast a growing number of women did select this option. Perhaps forty percent of the Quaker women in Philadelphia abstained from marriage, and the rate in Massachusetts was known to be above the national average. It was so high that the governor of that state suggested shipping the "surplus" women to Oregon and California in the 1850s.

Of course for most women, passing up on the chance for a marriage was unsatisfactory. Motherhood without marriage could only be attained sinfully and at tremendous social scorn. To support a child on women's wages was also near impossible.

In antebellum times, the lack of a family was indeed the common price of independence.

Recommendations/Sources

- Gail Collins - America's Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines (P.S.)

- Alexis de Tocqueville - Democracy in America