Dangerous Cures and the Popular Health Movement

Marie Starling, January 29 2013

Thomas Cole - Home In The Woods (1847)

Thomas Cole - Home In The Woods (1847)In the early 1800s, most doctors were more likely to kill their patients than help them. The Popular Health Movement is the name given to a broad, loosely aligned coalition of medical reformers that arose in the 1830s to combat the worst excesses.

Various reformers advocated for an increased emphasis on exercise, whole grain foods, vegetarianism, clean water, temperance, and bathing. They also advocated for an end to medical licensing, which they saw as a tool to promulgate poor health care at the hands of an elite coterie of medical professionals. In the Jacksonian political climate they were able to effect this reform in most of the states.

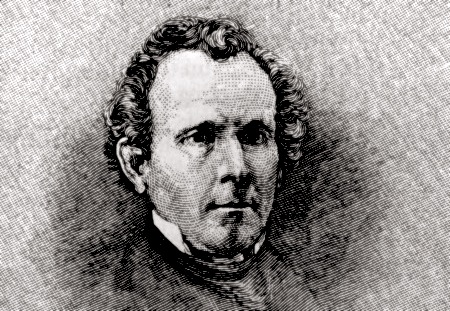

Perhaps the most famous health and diet reformer of this era was Sylvester Graham, the inventor of graham crackers.

Mainstream medicine in the Jacksonian Era

Medicine in the early 1800s was a gruesome spectacle, succeeding by the placebo principle in the best cases. Between massive and frequent bloodlettings, ignorance of germs and infection, the common use of mercury pills and laxatives, and a reliance on often unclean forceps in the field of obstetrics, mainstream medicine was one of the biggest obstacles to good health in existence during the early history of the United States.

Bloodletting

Bleeding patients was unfortunately an extremely common practice in the early United States. The practice is now even considered to be the cause of George Washington's death -- he was drained of five pints in two days after falling ill.

Sometimes leeches were used, and sometimes other medieval-looking contraptions that were invented for the purpose. The intellectual foundation was the "four humors" health philosophy of Hippocrates and other ancient Greeks. It was held that the healthy body had a balance of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Removing blood from the body was held as a way of restoring this balance.

Calomel

One of the most commonly prescribed medicines during this era was calomel -- a type of mercury pill that stimulated the bowels.

Unfortunately, as is now well known, mercury is a highly poisonous mineral. Some short and long-term symptoms of ingesting it include discolored skin and eyes, skin peeling, brain damage, and renal failure. Even in the early 1800s there were people who were skeptical of calomel's medical benefits, but their opinions did not influence standard health practice until many decades later. As late as the Civil War, both armies stocked large supplies of calomel for their field hospitals.

To aid in ingestion, calomel pills were sometimes mixed with honey, molasses, julap powder, or other elements. They were also sometimes adulterated with lead.

One medical debate at this time was between the "large-dose" and "small-dose" proponents of calomel. Some medical doctors believed that the substance worked best when administered in a single dose of large quantity. Others believed that this overwhelmed the patient, and thought it better to administer a series of small doses over time.

Obstetrics

Women were subject to a special array of gruesome procedures that men were fortunate to elude. Though childbirth had always been dangerous in America, infections became even more frequent in the early 1800s. This happened as the birthing process became professionalized and doctors took the place of midwives.

What we now recognize as puerperal fever was devastating to 19th century women. Forceps were often used in childbirth, but without any knowledge of sanitation they were usually dirty. Even the simple act of a doctor washing one's hands was uncommon.

Caesarian sections were rare, and few were qualified to perform them. They usually led to infections for the same reasons outlined above. Instead babies were delivered sideways or feet first if necessary, as there was little alternative. The more skilled doctors could diagnose a lost cause and cut a stillborn baby apart as it was being delivered, but the tools used to do so only increased the chances of fever and disease. There was almost nothing that could be done in cases of premature birth or complications.

When women became infected from these myriad hazards, it was very common to bleed them out. Multiple pints of blood were sometimes removed in a single day or even a single procedure. This obviously provided little benefit to any woman who was struggling for her life in the aftermath of childbirth.

Overall, the infant morality rate was well over 200/1,000 live births in the early 1800s, and that number was probably over 300 for black women. For the women itself the process was marginally more safe -- perhaps 1 in 25 or 30 women died of childbirth during their life.1

1 - These are all very rough estimates.

The American Diet in the early 19th century

If the health care that people received was of horrible quality, the typical diet consumed was little better. Water, milk, and meat alike were often highly contaminated and they contributed greatly to America's poor health.

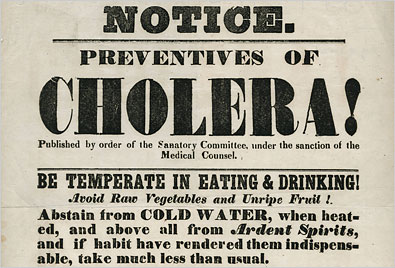

At a fundamental level, there was little appreciation for the benefits of a clean water supply which especially impacted people living in cities. Cholera, a water-borne disease, swept across the country several times without remorse. The most brutal of these epidemics were in 1832 and 1849, killing an estimated 150,000 people. Most of these deaths could have been avoided had people been aware of the need to keep clean drinking water.

Alcohol consumption was probably at its highest level in American history during the 1820s and 30s. The average person drank a full 5-7 gallons of alcohol per year (one estimate is 7.1/year) -- roughly three times the modern level in the United States, and greater than modern consumption in Russia, Ukraine, or Moldova. Hard liquors such as rum, whiskey, and bourbon were the most often consumed, as well as cider.

Those who lived in cities also dealt with contaminated milk, unsafe bread and meat, and overcrowded living conditions. Many health experts also argued that fruit and vegetables were unhealthy. The average diet of the time was particularly greasy and problems with digestion were common.

The Popular Health Movement

Needless to say there was plenty to critique in this medical system. In the democratic environment of the 1830s an array of reformers and alternative physicians arose to challenge the established medical hierarchy. They have been collectively labeled the Popular Health Movement.

This was not a centrally organized movement, and individual practitioners differed widely on the advise they dispensed. As a whole, however, this group focused on the benefits of exercise, moderation in alcohol consumption, and dietary reform as paths to better health. Many advocated for a return to midwives over doctors in the area of childbirth. Some also criticized the over-reliance on pills and concoctions -- a critique that was quite prescient in hindsight. Nearly all of them were intermixed with the excitement surrounding the Second Great Awakening. There were often religious or even millenarian overtones to the calls for clean living.

The Popular Health Movement also worked to end the power of states to license medical professionals. While this would be anathema to modern sensibilities, the licensing process was wrought with fraud and elitism in the early 1800s. There was a clear class and political divide on this issue -- the Democrats favored the right of any man to practice medicine while the Whigs usually favored licensing and regulations. As the Democrats swept to power in the 1830s they generally ended the monopolies on medical practice.

Sylvester Graham

Sylvester Graham was probably the most famous health reformer of the 1830s. By traveling and lecturing extensively, he built support for his ideas and gained a devoted following, particularly in the North.

One of Graham's central ideas was vegetarianism. He was one of the first prominent individuals to advocate this as a lifestyle, and while few of his followers adhered to the vegetarian way without fail, they did try to eat more grains and vegetables and less meat. Graham also crusaded against the use of processed and refined flour in bread. His legacy has best survived to the present times in the form of his "Graham cracker", which was a bran-infused whole grain foodstuff. Ironically, the modern, sweetened variant of the graham cracker would be appalling to Sylvester Graham's sensibilities.

Religion was central to Graham's teachings. In addition to his lectures on diet he was an active Presbyterian minister. Diet, health, and upright character were intertwined in his eyes. Thus he counseled the avoidance of spicy foods, since they might give rise to temptations of the character. He also opposed the consumption of alcohol, and lectured to young men on the ideals of chastity and the avoidance of masturbation, which he believed to be a cause of blindness and mental decay.

Graham's travels did not proceed without controversy. Some in the press labeled him as a fanatic and a charlatan, while angry groups of butchers and bakers broke into and disrupted a few of his lectures. But he also won many followers who went on to explore herbal cures and alternative diets in their own right.

The huckster element of 19th century medicine

Unfortunately, many quacks and hucksters took advantage of the times to defraud the populace. The patent medicine craze led to a number of itinerant cranks who sold dangerous (or at best useless) concoctions to make a quick buck. One infamous example was William A. Rockefeller, who was the father of a certain John D. Rockefeller in western New York. It is from these types of people that the term "snake oil salesman" arose in American parlance.

However, as a whole the Popular Health Movement was well-intentioned and opened up a long and fruitful history of critique against establishment medical practice. If the solutions proposed sound quaint or misguided by modern standard, it's important to remember that the movement was limited by the sparse medical knowledge of its era.