Teddy Roosevelt and the Coal Strike of 1902: A New Era in Labor and Government

Dan Bryan, February 8 2015

In most of the strikes in the late 1800s, the United States government either did not intervene, or went so far as to intervene on the side of management. Federal troops were used in the great Railroad Strikes of 1877 and 1894, for instance. However, the actions of Teddy Roosevelt in the Coal Strike of 1902 set a new tone in labor-government relations. This became a centerpiece of Roosevelt's progressive reputation in the coming years and showed that Republicans as well as Democrats could respond to the era's zest for reform.

An Anthracite Coal Strike in Eastern Pennsylvania

Coal was a very common method of home heating in the early 1900s. Often there would be a central stove connected to a ventilation system, with a steady supply of fresh coal needed to keep the system working. There was no real backup material at that time. It would not be until the 1920s and later that coal was widely challenged as a home heating material.

The coal-mining region of Eastern Pennsylvania rose to meet this demand. There are two primary types of coal -- bituminous and anthracite. While bituminous coal is easier to ignite and more commonly found in the United States, anthracite coal is the superior product when it comes to providing heat. The eastern region of Pennsylvania contained (and still contains) the largest deposits of anthracite coal in the United States, and was furthermore located conveniently to all of the major Northern, industrial cities of the early 1900s.

Coal miners had a number of grievances related to the work they performed. Coal was extracted from deep shafts and the process was labor-intensive. Hazards abounded. Two hundred people or more died in a single incident at Scofield Mine in Utah, in 1900. In the country as a whole, well over a thousand miners died each year, from 1900 all the way through the end of World War II.

Pay was also a serious issue. Labor shortages had been solved in with the use of immigrants from Europe. Hours were long. Operators of the mines were not disposed to compromise on such issues. In 1900 there had been an incident between the Pennsylvania miners and the mine operators, and the operators had been pressured to make concessions by the McKinley presidential campaign -- lest a strike cause bad press in his reelection contest.

The union representing these miners was the United Mine Workers of America, led by John Mitchell. In early 1902 this union made demands for additional wage increases and an eight hour workday, and the resulting impasse led to a strike on May 12th. 147,000 workers left their jobs on this day, determined to press their position to the utmost. Mine owners, led in this contest by George Baer of the Pennsylvania and Reading Railroad, were equally determined to dig in, without the distractions of a national election to pressure them into further concessions.

The Strike Drags On, and Roosevelt Steps In

At first, there was little reason to believe that this would be any more remarkable then the myriad other work stoppages of the era. The longer the miners remained off the job, the more the mines fell into disrepair. Yet most of the mine owners assumed that the strike would collapse if they maintained their own resolve. Hired guards of questionable quality and scruples (see The Coal and Iron Police) surrounded the mines, while the strikers intercepted and harassed incoming trains and threatened the lives of any "scabs". As summer turned into fall, it became clear that no quick solution was forthcoming.

Watching from Washington, Teddy Roosevelt became increasingly alarmed. The cost of coal in the United States continued to increase, putting consumers and businesses alike at the mercy of a shortage. Public anxiety about the prospect of a winter without coal was beginning to make itself felt.

Additionally, this was at the beginning of a great Progressive era in American politics and society. Where just eight years previous, Grover Cleveland had dispatched the U.S. Army to end a railroad strike in Illinois, Roosevelt now had different ideas. Using his personal and political connections, he was able to establish a commission to settle the issues brought forth in the strike. The initial meeting took place on October 3rd with all the key actors, and it was decided that a longer-term investigation would commence. In return, the miners returned to work on October 23rd, in time to ensure a steady supply for the winter.

The Anthracite Coal Strike Commission.

The Anthracite Coal Strike Commission.At the same time, the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission began its work. After much political wrangling this commission eventually ended up with seven members -- including one labor union man whose official role was "eminent sociologist". This commission interviewed 538 people in the coal industry, both workers and management, over the course of three months. They also extensively toured the Anthracite Coal Region of Pennsylvania. Their final verdict was a ten percent increase in wages and a ten percent decrease in working hours (from ten to nine per day).

The Legacy of the Strike

Politically, Roosevelt's strong intervention worked to his advantage. Many third-party businesses had been dependent on the coal industry and were not completely opposed to the Roosevelt stance. The incident played to Roosevelt's reputation as a vigorous, action-oriented President, and Roosevelt himself did not shy from expressing his opposition to corporate monopolies. He easily won re-election in 1904 against a more conservative, "Bourbon Democrat" opponent.

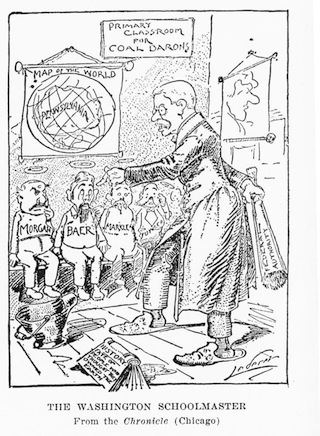

Roosevelt stands up to the coal barons. A political cartoon.

Roosevelt stands up to the coal barons. A political cartoon.The longer-term effects of the strike were just as important. Where the federal government in the past had been strongly pro-business in such labor disputes, it now acted in a more neutral manner. This portended a shift in mentality that eventually led to much increased regulation such as the Hepburn Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act.

It would be decades before unions won full protection and recognition in the eyes of the federal government. The Wagner Act of 1935 was the capstone in that regard, driven by the perils of the Great Depression. However, if that process had a beginning point, it could be said to be the strike of 1902 and Teddy Roosevelt's response.

Recommendations/Sources

- Theodore Roosevelt - The Autobiography of Theodore Roosevelt

- Edmund Morris - Theodore Rex

- Andrew Roy - A History Of The Coal Miners Of The United States, From The Development Of The Mines To The Close Of The Anthracite Strike Of 1902

- John Stuart Richards - Early Coal Mining in the Anthracite Region by Richards, John Stuart. (Arcadia Publishing,2002) [Paperback]