The Pullman Strike of 1894 and Labor Day

George Pullman was an exemplary nineteenth-century businessman. His railcar company dominated passenger traffic, and his factory supported an entire company town, fittingly named Pullman. His factory workers lived in company housing and shopped at company stores. Pullman created his town as the industrialist response to the utopian agrarian colonies of an earlier era. He imagined his town to be a new experiment in American community living. Yet, in 1894, it would be the epicenter of one of the United States's largest labor strikes in its entire history. The 1894 Pullman Strike was suppressed only with the power of the U.S. Army.

Pullman sleeping cars had a national reputation from shortly after the Civil War. Affixed to the lines of many railways, they provided modern comfort and exceptional service. The demand for these cars steadily increased, and Pullman expanded his production facilities to accomodate it. He became a rich man and his company became a beacon of the American industrialization.

George Pullman was far more than a mere industrialist. He had a vision to revolutionize the way of life for America's workers. To be sure, it was a vision that suited Pullman's beliefs, and lined Pullman's pockets, but the vision was there none the less. In 1880 he began the construction of an entire town for his factory and workforce. All of it would lie on 4,000 acres of Pullman land, wedged between Chicago, Lake Calumet, Lake Michigan, and the Indiana border. He supervised the construction of his own houses, theaters, parks, shopping areas, library, and hotel. He kept out saloons, political agitators, national newspapers, and the like to the best of his ability. Workers in the town paid Pullman for their rent, their groceries, and their clothes. They paid for this out of their wages from Pullman's factory. It was the American planned community at its most grandiose and overweening excess. It was the very incarnation of Jefferson's industrial nightmares from a century before, antithetical to any belief in liberty for the common man.

During the boom times of the United States, Pullman prospered like few others. The 1880s were a decade of economic prosperity mixed with frantic railroad construction, and few were better positioned than George Pullman to take advantage. To be sure, his housing was very high quality by the standards of his era. The rents were expensive, but the returns on investment modest (between 4-6%). In an era when several families could cram themselves into a single small tenement, Pullman's families enjoyed indoor plumbing and lived in two to seven room houses. Pullman himself believed that happy families led to better workers, and seems to have sincerely believed in the larger social mission of his community -- that it could shine light on new possibilities for the American system to perfect itself. But all of it lay on the bubble of prosperity of Pullman's sleeper cars.

The Panic of 1893 changed everything. Railroads across the nation went bankrupt, and their credit troubles rippled across financial institutions and banks throughout the nation. Millions were thrown out of work, prices collapsed, wages tumbled, and Pullman's business suffered greatly. To compensate, Pullman laid off a third of his workforce and cut wages for the remainder by 30% or more. He did this without cutting the living expenses in his town. He refused to negotiate these points, even though many workers were left with mere pennies to purchase essentials after spending their salaries on rent.

A strike broke out on May 11, 1894. At first consisting of Pullman's workers only, it would escalate in June. After weeks without progress, the Pullman workers appealed their case to the American Railroad Union. Eugene Debs, who led that union, supported the Pullman strike. Many other railroad workers supported it as well, and on June 26th they stopped moving trains with Pullman railcars. Within days, almost all rail traffic in the western part of the United States was halted. None could move through Chicago, with exceptions made for U.S. mail trains. To goad the federal government into intervening, U.S. mail trains were attached to all kinds of other cars by the railroads.

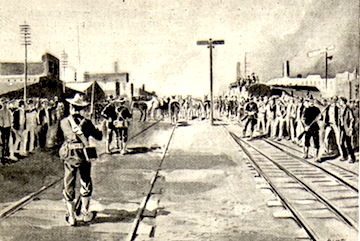

A court injunction was issued against the strike on July 2. When the strike continued, President Grover Cleveland dispatched federal troops to Chicago to restart the trains. Troops and militia battled with crowds of railway workers and sympathizers. Eventually, however, the situation left the American Railroad Union with little choice but to give up the strike. The episode became a heated political issue of the times. Many millions supported the intervention and believed that America's rail traffic must not be held hostage to the actions of labor unions. An equally fervent group saw nothing but despotism and tyranny in the actions of Pullman, Cleveland, and the other railroad companies. It would be decades before these fundamental tensions receded from the American political scene.

A federal commission investigated the strike, recommended more cooperation between business and labor in the future, and denounced Pullman's vision of his town as "un-American". In 1898 the Illinois Supreme Court ordred the town disbanded, and it was eventually annexed into Chicago. Additionally, to smooth the tensions over surrounding the strike, Grover Cleveland signed Labor Day into law as a federal holiday.