Prelude to Social Security -- The Rise of the Townsend Plan

Dan Bryan, September 24 2012

The Social Security Act was not in the first wave of New Deal initiatives, and it was not passed until 1935. Often forgotten is the immense pressure put on Franklin Roosevelt to implement a plan for old-age security, coming from a variety of sources. Foremost among these advocates was Dr. Francis Townsend of California, whose Townsend Plan gathered up to 5 million signatures in 1934.

A History of Old Age in America

The problem of caring for the elderly was not particularly salient through the early 19th century, for a couple of reasons. Most obviously, there were very few people in the 1800s who reached an advanced age to begin with.

- In 1850, a man who reached the age of 20 could expect to live another 40 years on average.

- In 1870, only 3% of Americans were above the age of 65.

Secondly, the agricultural economy did not displace the elderly nearly as much as industrial economy would by the early 1900s. When the primary means of sustenance was a family farm, the elderly were more likely to be landowners than the younger generations, and tasks could easily be rearranged to give less demanding work to those who needed it.

Both of these factors changed during the latter 1800s. Life expectancy increased, meaning there were more elderly people at risk of poverty.

- In 1900, 4.1% of Americans were above the age of 65.

- In 1930, 5.4% of Americans were above the age of 65.

More importantly, the nature of the American economy changed in a way that devalued the skills of older workers and removed their traditional safety nets. Accidents or injuries could no longer be covered for by relatives -- past a certain age they led to a complete loss of income. For as many years as they could, most people worked without respite. It is estimated that 75% of men over 65 were still working in 1880. The concept of "retirement" was largely non-existent.

The first private pension plans arose within the rail industry in the 1870s. There were about four hundred of them in place by 1930. There was also a public pension plan for Union Army veterans. However, the overwhelming majority of America's elderly were not covered by any type of plan, even by 1930. The fortunate among those people who were not able to work found lodging with relatives or old friends.

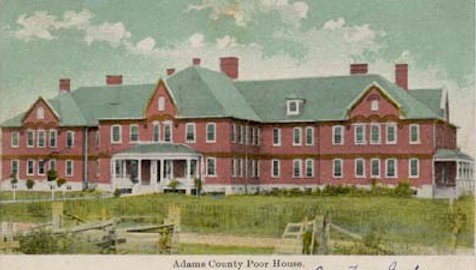

Poorhouses in America

What of those who couldn't make such arrangements? Care for these individuals was organized on a state-by-state basis. Generally the states established poorhouses to provide basic necessities for the indigent.

These buildings accepted anyone lacking means of support, but they were predominantly populated with the elderly. A Massachusetts study from 1910 found that 92% of poorhouse residents in that state had entered after the age of 60.

The poorhouses shared many traits of the modern nursing home at a more primitive level. While conditions varied from state to state, and even from county to county, they were generally bad. Medical care was basic, living conditions were spartan and communal, and recourse from neglect was non-existent. In popular conversation, the poorhouse was most certainly a place to be avoided.

The Rise of the Townsend Plan

It was in this environment that the Great Depression struck. As bad as the Depression was for most groups, it was terrible for the elderly. Pension plans folded or cut benefits, while the unemployment rate for workers above 60 approached 50%. All of the indignities of an old age lived in poverty began to multiply amongst the population, and in the chorus of voices calling for reform or radicalism there was that of Francis Townsend.

After working most of his life as a doctor, Townsend found himself broke and unemployed during the Depression. One day he saw three older women digging through the garbage in his alleyway for food. In September 1933, he proposed a plan that would have provided $200/month all citizens above the age of sixty, with the requirement that they spend all of it before the next check was issued. The idea of this program was to simultaneously provide for the elderly, while providing a demand-side stimulus to the larger economy. It was to be financed by a 2% tax on all transactions.

Within months Townsend Clubs had sprung up around the country. Petitions calling for the enactment of the plan circulated and were signed by an estimated five million voters. By the 1934 Congressional elections, support for the Townsend Plan was so strong that it became a primary issue in some races. Candidates who voiced support for the plan won their elections more often than not. Townsend himself was a household name, having shown the incredible potential of organizing the elderly into a coherent political bloc. It was a lesson that did not escape the notice of Franklin Roosevelt.

The Drafting of the Social Security Act

In the summer of 1934, as Townsend's clubs were gaining momentum, Roosevelt created a team which would eventually draft the Social Security Act. The final piece of legislation, creating what we know today as Social Security, was signed on August 14, 1935. Compared to Townsend's call for $200/month the initial benefits were miserly, and the first monthly checks weren't mailed until 1940. In this interval Townsend continued to exert his influence for higher benefits, and he played a hand in subsequent expansions of the program until the 1950s.

What became of those who opposed the Social Security Act? Alf Landon, the Republican candidate for President in 1936, made the repeal of the Social Security Act a key issue in his campaign. The Republicans pushed slogans such as this one heavily in the final weeks:

"Wage earners, you will pay and pay in taxes... and when you are old, you will have an I.O.U. which the U.S. Government may make good if it is still solvent."

Alf Landon won two states in the 1936 election.

Recommendations/Sources

- Andrew Achembaum - What is Retirement For?

- History of Poorhouses in America

- Sylvester Schieber and John Shoven - The Real Deal: The History and Future of Social Security

- Nancy Altman - The Battle for Social Security: From FDR's Vision To Bush's Gamble

- The Evolution of Retirement: An American Economic History, 1880-1990 (National Bureau of Economic Research Series on Long-Term Factors in Economic Dev)