The American Mafia in the Early 20th Century

Dan Bryan, March 8 2012

Italian neighborhood (Mulberry Street) in New York City, early 1900s.

Italian neighborhood (Mulberry Street) in New York City, early 1900s.There were rumors of something new and sinister in New Orleans. The Sicilians were behind it all, they said. The Sicilians who had crowded into the French Quarter and made their own, personal territory. There was a "war" between two rivals and then one day in 1890, it blew out in the open.

The police chief of New Orleans was shot dead -- "A dago..." were his dying words. The fury of the white New Orleans crowd was touched off by this revelation. 300 Italians were rounded up and arrested and sensational headlines emerged. America at large began to learn about the "mafia".

After nine acquittals blamed on jury tampering, a mob stormed the jail and attacked, killing eleven Italian prisoners. Two of them were hung from lampposts in the street, and the cheers of the crowd were said to be deafening.

Into the Great American Melting Pot

Four million Italian immigrants arrived in the United States between 1880 and 1920. With a lukewarm reception awaiting, most found themselves crammed into the urban ghettos of the big American cities. The most populous and famous of these was "Little Italy" on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was here that the most infamous mafias would be formed.

Life was rough for the new arrivals. They crowded into apartments that were usually decrepit. Men worked in construction and in the factories. Many women worked as seamstresses. Seventy hours a week was commonplace. Sunday was the only respite.

The first illegal activities were fairly simple, and they were usually directed at the Italian immigrants themselves. A letter would arrive, specifying an amount of money to be delivered to a given place. If the money was not delivered, the recipient of the letter would be assaulted or killed. Most commonly targeted were the owners of successful businesses.

Business of the Mafia

What did the mafia actually do?

Even before Prohibition, the organizations were becoming increasingly sophisticated. The first responsibility was always protection. When a storeowner or an individual paid money to a certain branch of the mafia for "protection", a bond was created between the two parties that entailed responsibilities. The mafia was to protect the storeowner from extortion by other mobsters, petty crimes, and problems with police or other citizens. In practice, the quality of the protection received could vary quite a bit.

Protection or tribute was the basis for all other mafia activities. If someone ran a prostitution ring in a certain area, they paid the mafia a share. If they ran an underground gambling establishment, they paid the mafia a share. The person doing this was often in the lower level of the mafia themselves, but sometimes they were independent entrepreneurs who paid their share to operate free of harassment.

With that explained, here are some of the things that the mafia was associated with, beyond everyday extortion of local businesses:

Alcohol - sales of alcohol during Prohibition are widely credited with giving mobsters power and wealth beyond their dreams. Al Capone may be the most famous of the 1920s gangsters, but many others were not far behind him, and it was in this era that the mobster first entered into widespread American consciousness.

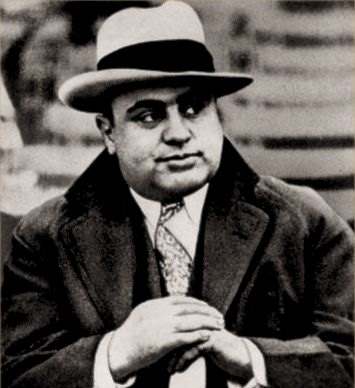

Al Capone of Chicago was the most famous mobster of the Prohibition Era.

Al Capone of Chicago was the most famous mobster of the Prohibition Era.Labor union organizing - many Italians worked in the shipping, construction, and trucking industries, and it was only natural that they should wish to organize. Independent attempts to do so were often crushed by management. Mafia intimidation helped to rectify this problem. As de facto leaders of many unions, the mobsters could profit in a number of different ways. For a time, no construction in New York City could proceed without their approval.

Robbery - Not so much petty street robbery. Through connections (in the unions and elsewhere), the mafia was often aware of when a valuable shipment would arrive through the ports, or via rail and truck. When this happened, the businesses doing the shipment could sometimes pay the mafia "protection" money not to harass their shipments, or they could be robbed. This was a win-win proposition from the mafia's point of view.

Gambling or "the numbers" - No state had a lottery in the first part of the 20th century. The mob filled this vacuum by operating "numbers" and taking bets. Numerous bookies handled these bets and provided a cut to the mob. An individual could also bet on baseball, boxing, horse racing, or other popular pastimes with the bookies. Though the numbers were much reviled at the time as a game that leeched money from the poor, the payout % on most state lotteries is lower than on the mafia's numbers game.

Prostitution - Self-explanatory. This was usually managed on the street level, with the mafia receiving a cut from the local pimps.

Loan sharking - The "six-for-five" loans became standard. Repayment was expected promptly, but could be delayed indefinitely if exorbitant interest charges were paid instead. The origin of the famous, "breaking of the knees" idiom.

Drug trafficking - In the early 20th century, the drug trade was usually confined a very small era of the city. Often this was by design of the mafia, who preferred to see it concentrated in the ethnic ghettos, in cooperation with the police departments.

Vice Districts and the Police

These endeavors made the mafia an organization that featured prominently in the lives of America's poor and of its lowlifes. Many of the businesses went hand-in-hand and supported each other. For instance, people might borrow money to purchase drugs or to gamble with. Those who owed money might tip the mafia off to a valuable shipment, if they had that knowledge, in return for leniency. Those who visited prostitutes could be extorted, if their position was of enough importance.

There was a massive amount of cooperation with the urban police departments, to the point that the line between cop and mobster could be fuzzy. The police did not have any hopes of eradicating alcohol consumption, gambling, or the associated vices so they endeavored to contain them in the "vice districts" of a city. These would always be in the poorer neighborhoods, and the very ones where the mafia was so firmly entrenched.

In return for a cut of the profits, the police became the protectors of the mob. It was easier to accept a hundred dollars to ignore a robbery, than it was to risk one's life in an attempt to arrest the perpetrators. The former course of action enhanced the prosperity and livelihood of the officer. In a way, it acted as a supplement to his salary that the taxpayers of the time were unable to provide.

The Mafia as an Inhibitor to Economic Activity

Who lost the most from these practices? Businesses of course. Businesses who had to pay more due to union violence. Businesses who saw their profits cut into from theft and extortion. Businesses who had to pay more for insurance due to insurance fraud on the part of mob.

In many cases, these were the same businesses who busted strikes when they could, who worked Italian immigrants to the bone, six days a week. Who looked the other way when safety violations occurred, even as men died on the job.

To the mob and their Sicilian brethren, this was hardly a concern. Life was seen as a brutal, violent competition where the strongest and craftiest survive at the expense of others. And they lived and died by that philosophy.