The Great (Farm) Depression of the 1920s

Dan Bryan, March 6 2012

The 1920 Census determined for the first time that more Americans lived in cities than in the countryside. The margin was narrow -- 51 to 49 -- but none the less it was a key turning point in our nation's history. It is probably not a coincidence that the 1920s are the first decade to contain a real, mythical focus on the exciting lives of the city dwellers in many history books.

What about those forty-nine percent who lived in the countryside? For them the 1920s were hardly a golden age. On the contrary, there was an agricultural depression that lasted the entire decade and kept a noticeable divide in place between this class and the urban classes. The women of the farms made great sacrifices in this time just to keep their families underneath a roof.

Overproduction and Price Deflation

The origins were both political and structural. Agricultural exports to Europe exploded during the Great War, and even this was not enough to keep up with demand. Corn, wheat, and cotton all hit very high prices, and this encouraged new tilling, new growing, and most importantly new borrowing. With a postwar price collapse came a rural financial collapse as well.

Structurally, the demand for rural farming and labor was dropping faster than people were able or willing to move out of the countryside. As the American economy was becoming increasingly mechanized and industrialized, there was simply not as great a need for half of the population to work on farms. But many people were attached to this way of life, economically, financially, culturally, and psychologically.

It was not easy to give this up -- overnight -- and move to a strange city with no connections, marked as a hick and an outsider. Thus, many stayed and tried to make it work, even in an era of severely depressed food and cotton prices. Often the result was foreclosure and abject poverty.

The women in these areas were not buying the latest rayon undergarments, nor were they trimming their hair and their dresses short, or enjoying the newfound glitz of the Jazz Age. They were still sewing their own clothes, patching holes in their husbands' shirts, and making dresses stretch from one daughter to the next. They still slaughtered their own meat, grew and canned their own vegetables, and in many places bartered for what they could not produce. Survival skills took precedence over cultural sophistication.

The social safety net was the kindness of relatives, neighbors, and the church. It was not uncommon for more than one family to share the same house, or to take in boarders as times got hard.

1919 Strikes and the decline of labor unions

Immigrant women had lived a rough life for decades, and that did not change in the Roaring Twenties. While there was a broad increase in prosperity for the economy at large, the benefits to the industrial class were mixed. Working women were especially affected because they were concentrated in the garment and textile industries, which were in decline throughout the decade.

Politically, organized labor lost a lot of power and influence after a series of failed strikes in 1919. The largest of these was a nationwide steelworkers strike, in which 350,000 workers struck against the US Steel Corporation. Most of them were immigrants and the press was quickly able to portray them as radicals, in sympathy with the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. The strike was a colossal failure, as were all the other big strikes of 1919. It was during that year that a man named Calvin Coolidge made a national name for himself in opposing and defeating a police strike in Boston, while serving as Governor of Massachusetts.

The overall effect was to slow the increase in wages for the working-class, which kept working class women and men on the margins of the American prosperity that was emerging in this era.

Declining wages in the textile mills

Consequently, many women of the immigrant classes remained in the center of the big cities, crammed into tenements with any number of extended relatives, boarders, and small children. While it would be a stretch to say that life got worse compared to previous decades, it was hardly improving for them at the rate that it was for many others. They were less likely to be using electricity, appliances, didn't own cars except in rare occasions, and certainly wouldn't dream of taking their clothes to a professional laundry. And all the time, jobs and pay for textile work were decreasing, forcing ever more of them into domestic work.

Some women's unions attempted to strike in the 1920s as well, but their attempts were also disastrous. There was a large strike in the garment industry in 1924. After it was defeated, many jobs moved down into the south, where unions were less of a problem. The logic for this transition was simple -- longer hours at lower pay. Dorothy Brown states that, "In 1926, while the average New England textile worker earned $21.49 for a forty-eight-hour week, the average worker in the south earned $15.81 for a fifty-five-hour week."

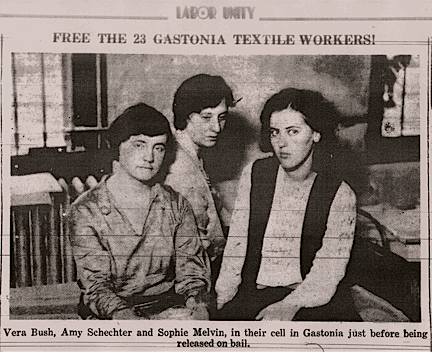

The Gastonia, North Carolina strike of 1929 was a failure.

The Gastonia, North Carolina strike of 1929 was a failure.Two strikes in 1929 among the southern textile workers both ended in failure. One took place in Elizabethtown, Tennessee. The other was in Gastonia, North Carolina. Wages didn't budge in either case.

Discrimination against black women in the south and north

These were just the problems that white mill workers encountered. Black women in south could be hired at the mills, but only to do things like sweep the floors or clean the machines. They were never hired to operate machinery unless their services were needed to fill in during a strike -- i.e. to serve as an example to the ungrateful women and girls who usually held those jobs. They would often be lucky to make ten dollars in a week.

The greater part of black women in the south were still a part of the sharecropping system. Running a brutal arrangement in the best of times, the landowners were put under heavy strain by the fall in cotton prices and real estate values. If they had held the best of intentions towards the black community, they still could not have offered much in their work contracts. Many southern white families, including their women, were also forced to work as sharecroppers after the price collapses and foreclosures.

Blacks of both genders left the south in large numbers during the 1920s. When the black women arrived in the north, they were excluded from most of the jobs that other women could hold. A large part of them became maids. Whether man or woman, all blacks who moved to the north started at the bottom of the economic spectrum, and they were usually reviled by the immigrants with whom they competed with for jobs and wages.

Recommendations/Sources

- "The 1920s - Not Roaring in South Carolina"

- Gail Collins - America's Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines (P.S.)

- Dorothy Brown - Setting a Course: American Women in the 1920s (American Women in the Twentieth Century)

- Frederick Lewis Allen - Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s