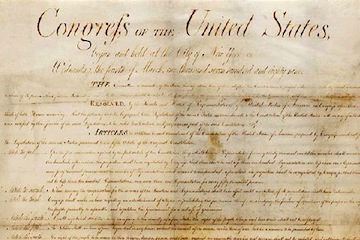

The First United States Congress and the Bill of Rights

Today the Bill of Rights is a sacrosanct part of the American legal system. Yet when the Constitution was put forward for ratification, many argued that a Bill of Rights was superfluous or redundant. It was Anti-Federalist opposition that led to the promise of a Bill of Rights. It was left to the First United States Congress to make good on this promise. Meeting for its first session in 1789, the Congress passed twelve amendments on September 25th and sent them to the states for ratification. Ten of these amendments became the Bill of Rights, one was ratified in 1992 as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, and the final one remains unratified to this day.

During the period of ratification, some very prominent spokespersons denounced the new Constitution and called for a Bill of Rights at minimum. Such individuals included Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, Richard Henry Lee, and Elbridge Gerry. Gerry in particular made his support of the Constitution conditional on a Bill of Rights, without which he feared a quick descent into tyranny from the national government. Some who favored the ratification of the Constitution in its own right were also disposed to support a Bill of Rights. Massachusetts and Virginia sent proposed amendments along with their ratification, and James Madison was a Federalist who came to support a Bill of Rights in the spirit of compromise.

It is to all of these individuals that we owe the First Amendment, protecting free speech and the free exercise of religion. Or the Second Amendment, protecting the right to bear firearms. Or the Fourth Amendment, protecting Americans from unreasonable searches and seizures of property. The Sixth Amendment provides the right to a speedy trial, the right of a defendant to call witnesses, and the right of a defendant to an attorney. The Eighth Amendment protects the convicted from cruel and unusual punishment. The Supreme Court would later rely on these Amendments heavily in its defense and expansion of individual rights, particularly in the areas of free speech, birth control, and criminal law.

In comparison to how much time has passed since 1789, it often seems like the Bill of Rights was instantly passed along with the original Constitution. However, this is not the case. Congress first met in March of 1789 and it was only in September that the Bill or Rights was passed and sent to the states for ratification. The first ten Amendments were not ratified until December 15, 1791. Thus, we did have a federal government under the United States Constitution for almost three years that operated without the Bill of Rights. Imagine the media outcry that might take place today during those three years, as the nation awaited ratification.

One amendment passed by the First Congress was not ratified by the states until 1992! The Twenty-Seventh Amendment prohibits any change to the salaries of Congress from taking effect until at least one House election has occurred. For instance, if Congress passed a law doubling their salaries in 2015, the salary increase would not take effect until a new Congress met in 2017. Thus, eleven of the twelve amendments initially passed by the First Congress have now been ratified.

What is the remaining amendment? The one which was never ratified? It is an amendment to fix the representation of Congress in proportion to the population. If ratified today, it would require the House of Representatives to have at least 200 members, and no more than one member for every 50,000 people. Based on the 2010 Census, this would allow up to 6,174 Representatives. The House has been set at 435 members since 1911, so these limits would have no effect on the current House if the amendment was ratified. However, the original wording of the amendment specified that there should be no less than one member for every 50,000 people. If this were in force today, then the House of Representatives would be required to have at least 6,174 members. This would certainly have interesting implications for modern politics, for better or worse.

Taken as a while, the Bill of Rights are a cherished part of the national tradition. To question their necessity, as Alexander Hamilton did in his time, would be a heresy beyond the pale of American politics.