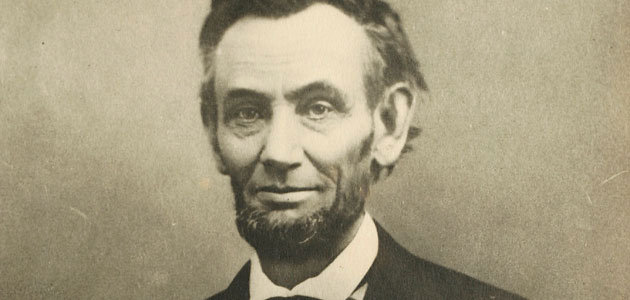

The Emancipation Proclamation -- A Legacy Deserved?

Jonah Phillips, January 18 2015

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1862 is often hailed as a landmark of America's Civil Rights struggle, declaring freedom for slaves and beginning a long road of increased respect for black rights that eventually led to Martin Luther King's march on Washington and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This article aims to determine whether the Emancipation Proclamation deserves its exalted legacy by examining the causes behind Lincoln's decision to issue it and the effects it had.

The Emancipation Proclamation was not an order abolishing slavery. The states in the Union where slavery was legal were exempted from it. Portions of the Confederate states that were controlled by the Union army were also exempted. Slaves liberated by Union soldiers from Rebel owners were also unaffected: they were considered “contraband” and were often shipped northward to non-slave states to work as farmhands and laborers replacing the men conscripted into the Union army. Importantly, the only states affected by the Emancipation Proclamation were members of the Confederacy, where Lincoln had no authority.

If Lincoln did not free any slaves with the Emancipation Proclamation, why issue it? And why announce it on September 22, 1862 but not have it go into effect until January 1, 1863? The reason is that the Emancipation Proclamation specifically freed slaves in states currently in rebellion against the Union. If a state in the Confederacy were to voluntarily return to the Union before the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, its right to maintain slavery within its borders would be preserved.

Why would Lincoln issue such a measure? Why sacrifice one of the Union's goals in the Civil War to lure Confederate states back to the Union? The short answer is that the war was not going well. General George McClellan, in charge of the key Army of the Potomac, was consistently slow to move and reluctant to engage Confederate armies, regularly overestimating his enemies' forces and refusing to advance without more supplies and more troops. In the West, meanwhile, Union armies had been unable to open the Mississippi river, which was a key waterway for supply lines and regional trade.

Lincoln needed to turn the tide on the battlefield, and his armies were insufficient. He wanted a quick end to the fighting and a restoration of the Union, and hoped that the Emancipation Proclamation would lure enough states of the Upper South back to the Union to regain military advantage by promising to leave slavery intact in those states. In the best-case scenario for Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation would preserve slavery, not end it.

This is not to say that Lincoln was in favor of slavery. Lincoln disliked slavery on a personal level, but considered the eradication of slavery a less important aim than maintaining the Union. Writing a public response to an editorial by the prominent Abolitionist editor Horace Greeley, Lincoln wrote:

This had been Lincoln's stated position from the start of the Civil War, and it was a shrewd one. Lincoln was a clever politician, and he recognized that framing the war as a war against slavery would alienate the Democrats, who had strong support in the slave states in the Union: Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. Stalemated militarily, a defection of one of these states could easily turn the war in favor of the Confederacy. Additionally, the Moderate Republicans who predominated in Northwestern states such as Illinois and Indiana favored maintaining the Union on constitutional grounds, but had no strong abolitionist sentiment and sometimes had cultural or family ties to the South. Only the self-styled Radical Republicans who dominated the Northeast were dissatisfied with Lincoln's course, wishing he would declare abolition as the objective of the war.

The Emancipation Proclamation spurred a political realignment. Despite a goal of luring states of the Upper South to the Union (which was poorly supported by additional diplomacy and completely failed), the Emancipation Proclamation shifted the perception of the war to be a war about slavery, instead of a war against rebellion. As expected, the Radical Republicans were thrilled. Within the Democratic party, the War Democrats were undercut and the Peace Democrats gained prominence, as their support for the war was predicated on the argument that the war was not about slavery. Meanwhile, the Moderate Republicans of the Northwest were concerned about an influx of freedmen that emancipation would create, somewhat due to concerns about lowered wages but mostly due to racism.

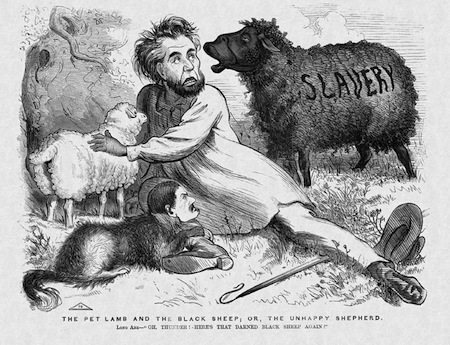

"Oh Thunder! Here's that darned black sheep again!" - A political cartoon from the Civil War era depicts Lincoln's struggles with the slavery issue. (click for source)

"Oh Thunder! Here's that darned black sheep again!" - A political cartoon from the Civil War era depicts Lincoln's struggles with the slavery issue. (click for source)Lincoln's subsequent promise in the presidential campaign of 1864 to push for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery (what became the Thirteenth Amendment) can be seen as a natural result of the political realignment caused by the Emancipation Proclamation. Having lost the support of some Moderate Republicans and many more Democrats, Lincoln needed the fervent support of the Radical Republicans. The Radical Republicans were still skeptical of Lincoln's earlier moderation, and pledging to support a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery would prevent them from supporting another candidate.

Historians are divided as to whether this cynical view of Lincoln's motivations is accurate. Lincoln's proponents point out that he had already written a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation when he issued his public rebuttal to Horace Greeley. They argue that the staunchly moderate rebuttal did not reflect Lincoln's views, and instead was part of the groundwork for framing the essentially radical Emancipation Proclamation in a way that moderates would find palatable. Alas, the great skill with which Lincoln was able to appear both moderate and radical has left historians not much better off than his contemporaries in knowing his true loyalties.

Test your knowledge with an Emancipation Proclamation crossword puzzle! Or, visit this page to work on the crossword below in its own browser window.

Created and powered by the Crossword Hobbyist crossword puzzle maker.

Recommendations/Sources

- David Herbert Donald - Lincoln