The Cuban Missile Crisis, an Ultimate Poker Game

Dan Bryan, February 14 2015

"A man who couldn't hold a hand in a first-class poker game isn't fit to be President of the United States." - Albert Upton

Poker has often been used as a metaphor for high-stakes confrontations, and for good reason. Many American Presidents made the game a favored past time and even used it to analyze the people they worked with. The analogy of a poker game is often used to describe Nikita Khrushchev, John F. Kennedy, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Ironically, Kennedy was one of the few Presidents of his era who had little interest in poker.

Certain concepts of aggression and people-reading were on display between Khrushchev and Kennedy at the Vienna Summit of 1961, as well as during the Cuban Missile Crisis itself.

The Hard Life of Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev was born in 1894 to two impoverished peasants on the Russian plain. Even by the standards of Russia at the time, his home town of Kalinovka was destitute. He went to primary school for four years, and then became a metal worker in Ukraine. After a few years of this, he became combatant and survivor in the Russian Civil War.

Khrushchev spent most of his adulthood in what could only be described as a stressful working environment. Throughout the early 1930s, he rose rapidly in the ranks of the Communist Party until he held a high post in Moscow city government. Then, in 1937, Joseph Stalin purged the vast majority of the high level Party apparatus. Khrushchev's survival seems to have come equally from shrewdness, ruthlessness, and good fortune.

Khrushchev probably proved his loyalty to Stalin as well through vicious attacks on the Ukrainian population. He survived the purges, only to find himself seemingly doomed again during the war with Nazi Germany. As a commander in Kiev, in 1941, Khrushchev was trapped in the largest encirclement in the history of land warfare. Nearly 700,000 Soviet troops were surrounded on the field, of whom around 150,000 managed to fight their way out. Khrushchev was lucky, needless to say, to have found himself with a group that escaped. Most of the remaining 550,000 were shot on sight, starved to death in open air prisons, or transported west to serve as slave labor.

If anyone was predisposed to view a confrontation with John Kennedy as a walk in the park, it would have to have been the Soviet Premier.

The Upper-Class Life of John F. Kennedy

Kennedy himself had a brush with death during World War II, in the Pacific Theater. The patrol boat he commanded was completely destroyed, leaving Kennedy and his crew stranded at sea. Kennedy swam three and a half miles while towing another crew member, all with a ruptured spinal disk. He was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his efforts.

At other points in his youth, Kennedy lived a life of relative ease, particularly for a child of the Great Depression. His father, Joseph Kennedy, was a millionaire businessman and the first Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission. While Khrushchev was sweating out his very survival in the 1937 purges, John Kennedy and a friend were making a ten week drive through France in a convertible. He was known in prep school and at Harvard as a bit of a rakish troublemaker, and certainly as someone who chased the girls. It was not until he was 36 years old that Kennedy got married, and even then it was likely to maintain a future in American politics.

There was a serious side to Kennedy as well, however. He did pick up his studies during his last two years at Harvard, and in so doing developed a keen interest in international affairs. His work ultimately resulted in the publication of Why England Slept, a study of appeasement in 1938.

Even so, as a relatively young President from the background that he had, Kennedy's experience could not compare to that of Nikita Khrushchev. Against the advice of many advisors, Kennedy was eager to hold a one-on-one discussion with Khrushchev after his election to the Presidency. Arrangements were thus made for a meeting in Austria.

The Vienna Summit

Khrushchev and Kennedy met for the first time in Vienna on June 4, 1961. This meeting was called The Vienna Summit. After some pleasantries the discussion turned to Berlin and Laos, and in these areas the two men quickly came to an impasse. At the same time, they took measure of each other and Kennedy did not acquit himself well. Khrushchev verbally pummeled Kennedy on colonialism, foreign policy, and European military bases in front of an international press contingent. Kennedy's responses had been ineffectual, and even he himself was so ashamed of his performance as to call it the "worst thing of my life".

Kennedy and others worried that Khrushchev had formed a low opinion of the American President, and would now be much more likely to undertake offensive action to test the United States. Kennedy himself said, "He just beat the hell out of me. I’ve got a terrible problem if he thinks I’m inexperienced and have no guts. Until we remove those ideas we won’t get anywhere with him."

The Cuban Missile Crisis

Mere weeks after the Vienna Summit, Khrushchev commenced building of the Berlin Wall. Overnight, on August 13th, Soviet troops appeared and began clearing a ring around the city on which to begin construction. There was little that the United States or anyone else could do about it.

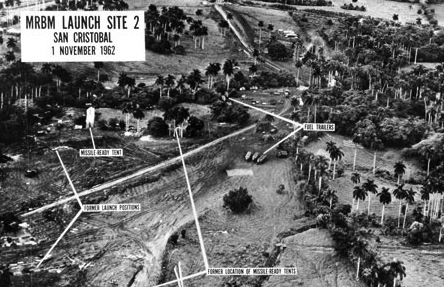

The bigger crisis began on October 16, 1962. On that morning, Kennedy was informed that Soviet missile installations were being constructed in Cuba, 90 miles from the Florida coast. Cuba was a newly Communist state at the point, after the ascension of Fidel Castro in 1959. Some suggested bombing or invading the island, while others raised the possibility of a naval quarantine.

On the 18th, Kennedy met with the Soviet Foreign Minister in the Oval Office, and repeated his admonition from the month before that the "gravest consequences" would follow from the introduction of offensive weapons into Cuba. However, Kennedy did not reveal what the U.S. already knew. This of course took a convincing act of omission on his part.

On October 22nd, however, the course of action was revealed. Kennedy made a nationally televised address revealing the presence of the missiles, and simultaneously established a naval blockade of Cuba. Khrushchev's reaction was furious -- he refused to acknowledge the quarantine and Soviet ships continued to sail for the island.

A driving principle of the negotiations over Cuba was brinksmanship -- the idea that the best outcome would be achieved by pushing events to the "brink" of disaster, without passing over that line. Here is where the element of poker comes into play. Most hands in poker never make it to a showdown (or "war", in the real world equivalent). Or in other words, all players fold at some point before the cards are revealed. It is in this gray area that the best players impose their will and make their fortunes, by constantly finding the limits to which they can push the action. Much the same principle was at stake in Cuba. Khrushchev had made an assessment of Kennedy and was now trying to push at the weakness he perceived to the greatest extent that he could.

In this case, however, Kennedy's resolve surprised Khrushchev. After a couple of days of maneuvering, Khrushchev offered to remove the missiles from Cuba in return for assurances that the United States would not strike or invade the island. This offer came in a letter. The next day a much more combative letter arrived making harsher demands of the Americans. At first unsure of how to proceed, Kennedy eventually ignored the second letter and proceeded along the dictates of the first.

And in the aftermath of this crisis it was Khrushchev, so wily and experienced from his long life, who came out looking weak and unprepared. Secretly, of course, the situation was much more balanced. The United States withdrew its own missiles from Turkey, and the Soviet Union really came out of the incident ahead of where it entered. But this was not publicized at the time.

In the world of perception, moreover, all the attention had been placed on Cuba and here Khrushchev was humiliated. In the most treacherous poker game of all, that of the Soviet Politburo, Khrushchev's credibility was greatly harmed. Less than two years later he was forcibly retired from his position in favor of Leonid Brezhnev.

As for Kennedy, his resolve throughout the Cuban Missile Crisis stands as one of his great points of in the eyes of his defenders. In the eyes of the American people, he emerged with a renewed burst of popularity that carried through the 1962 elections.

Recommendations/Sources

- Khrushchev and Kennedy: Vienna Summit 1961 (BBC documentary)

- Michael Dobbs - One Minute to Midnight

- James McManus - Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker

- William Taubman - Khrushchev: The Man and His Era

- Robert F. Kennedy - Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis