The Colorado Silver Boom and Silver Purchase

Dan Bryan, July 22 2012

A silver mine in Aspen, Colorado in 1898

A silver mine in Aspen, Colorado in 1898The myth of the rugged individualist has never gained more traction than when used to describe the early days of the American west. At the same time, the era in general is usually described as the apex of laissez-faire economics. Reality was more complex.

Currency policy (gold vs. silver) was a contentious issue in the late 19th century. It made Colorado's economy in the 1880s and broke it in the 1890s. Behind the scenes, that state's first boom was made by boosters and politicians who got the federal government to use silver coinage. When the program was ended due to financial pressures, the mines and towns of Colorado were devastated.

The expansion of the silver mines

It had been known that there was silver in the Rocky Mountains for many years, and the first small mines were opened in the 1850s. It was not for many years, however, that this practice took off and established itself as the chief activity of the area.

One catalyst was the Bland-Allison Act of 1878, which required the federal government to purchase two to four million dollars of silver each month from the western silver mines, and to circulate silver dollars as currency. Shortly thereafter a huge lode of silver was found in Leadville. As mining took off in that town and other places across the mountains, wealth spread its way across Colorado.

With obvious benefits to be had, western boosters and politicians were essential in the passage of Bland-Allison. Most area businessmen had at least some interest in the mines and they benefited directly. Others supported the idea for more general reasons. Because such a mining windfall would obviously increase the general prosperity of the area, there were very few people in Colorado who did not support silver coinage.

The result was an immediate silver boom in the region, with a corresponding increase in population. Denver grew from 35,629 people in the 1880 census to 133,859 in 1900. Construction proceeded at a frenzied pace and jobs were relatively plentiful both within the cities, and in the mining camps in the hills.

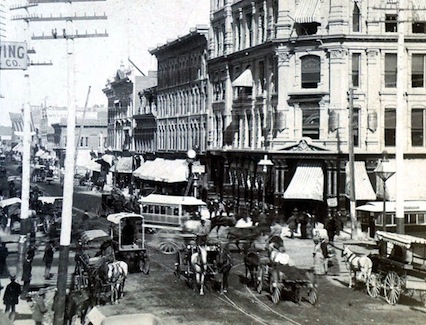

Denver in the 1880s

The Denver that resulted was at once opulent and brutal.

The largest houses rivaled those of New York and Boston, while much of the city operated without a sewer system. Smelters operated in the working class section of town. The smoke and dust permeated the town and obscured the mountains from view on some days, in spite of the fact that some were only twelve or fifteen miles away. Wild dogs roamed the dirt-packed streets, as did gangs of teenage hoodlums. So many people, and especially young men, had been drawn into the city in a short period of time that the infrastructure was overwhelmed.

Vice was endemic. Laws against prostitution were only enforced on the rare occasions when it was necessary to harass the local Chinese community. The same could be said for any laws related to liquor or the consumption of opium. The police force was underpaid and understaffed, leaving them quite vulnerable to bribery. "Soapy" Smith became a colorful figure in the area with his rigged card games and abundant payoffs to local officials. To add a personal touch to the proceedings, he hung a sign saying "Caveat Emptor" above the entrance to his saloon. For a brief time around 1890, he enjoyed a reputation as the boss of Denver's seedy underworld.

At the same time, magazines like Harper's Weekly proclaimed Denver "... a beautiful city -- a parlor city with cabinet finish -- and it is so new that it looks as if it had been made to order"

Such statements were made by those who lived or visited amongst the wealthy class of Denver society. In the 1880s, however, this was a sizable group. To those with investments at least, it seemed that nothing could go wrong.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act and the Panic of 1893

The heady days of the 1880s turned into a collapse in 1893.

The Bland-Allison Act was superseded by the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which was even more favorable to the silver mines. The minimum purchase amount was increased. Additionally, the Treasury was required to purchase silver with notes that could be also redeemed for gold. The value of the notes was fixed (at a rate of 1 oz. silver = 16 oz. gold). In practice this amounted to a subsidy of silver miners, since this fixed ratio gave them a higher price than their silver was worth on the open market.

Unfortunately for the citizens of Colorado, the Sherman Act proved itself to be untenable. Since the federal government paid more for the silver than it was truly worth, it consistently accumulated silver and paid for it with an outflow from the gold reserves. This was exacerbated by a financial crisis in Britain, which caused investors there to sell American securities and withdraw gold from circulation. When a market panic came in 1893, the federal reserves of gold were in danger of being completely exhausted, and were eventually saved only by the personal intervention of J.P. Morgan and the Rothschilds.

In this new environment the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was repealed (see Grover Cleveland's speech), and the consequences for Colorado were immediate. Coinciding with a general economic depression, the collapse of the silver industry turned Denver into one of the worst-hit cities in the nation. While the national unemployment rate was probably in the range of 12-15 percent, things were worse in Colorado. The poverty of Denver became more widespread and the tramps multiplied. Many of them turned to theft and crime to survive.

Drinking and debauchery was still rampant, but now such pastimes were indulged in not to celebrate life, but rather to deaden the senses against the calamity that had unfolded. It would be many years before Colorado regained the buoyant atmosphere that it had enjoyed in the 1880s.

After the repeal

Attempts to regain the favor of the federal government were unsuccessful. Traditionally a Republican bastion, Colorado gave William Jennings Bryan 85% of its vote in the 1896, but the staunchly pro-gold William McKinley was the man elected. It was clear that no return to silver coinage was forthcoming.

A Denver panorama, 1898

A Denver panorama, 1898In the following years, the people in that state began to build an economy based on other types of mining and on other ventures entirely. Businessmen sought to attract factories from other areas of the country, and the potential of the region for tourism was explored for the first time. Farming was given more emphasis and a program to encourage the growing of sugar beets took off. New mines were opened to exploit more mundane commodities, such as coal and lead. None of these resulted in a boom the way that silver mining had, but they collectively ensured the area's economic survival.

The experience of Colorado in the 1890s should serve a cautionary tale to the transience of economic booms, especially ones that are artificially based on the ability to influence policy and law in a favorable direction.

Recommendations/Sources

- Lyle W. Dorsett - The Queen City: A History of Denver (The Pruett Series)