Cavaliers and Roundheads -- The American Legacy of the English Civil War

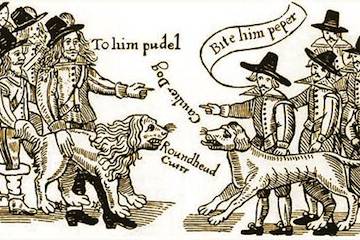

The first two areas of English settlement on the American continent were Virginia and Massachusetts. These colonies differed greatly in religion, politics, and culture. In the early days of America, many thinking people looked to the legacy of the English Civil War to explain these differences. Many who settled in New England had identified with the Roundheads -- those who fought against the monarchy and for Oliver Cromwell. On the other hand, Virginia was filled with Cavaliers -- sympathizers of the monarchy, or in some cases exiled combatants for it.

For many, these differences were derived from innate, racial distinctions. The Southern elite looked upon itself with pride as the descendants of England's Anglo-Norman invading class, who had ruled for centuries since the times of William the Conqueror. The New England region was conversely seen as Saxon-descended, filled with industrious, but common people who lacked the vigor of the Norman element. It was thus considered natural that the culture of the South would be honor-bound, manorial, and aristocratic. Or that the culture of the Northeast would be sober, puritanical, and industrious.

Many Americans, and even foreign visitors, were conscious of these "racial" differences until the Civil War. Louis Philippe of France wrote, "You have the Puritans in the North and Cavaliers in the South, Democracy with its leveling rod, and Aristocracy with slavery raising in the other section and creating a social elegance..."

Southern writers in turn produced statements such as, "This cavalier or Anglo-Norman element that had presided at the founding of the original Southern colonies entered largely into the new populations; ... mingling the refinement of the courtier with the energy of the pioneer." or that the South was settled by "a (Norman) race distinguished in its earliest history for its warlike and fearless character, a race in all times since renowned for its gallantry, chivalry, gentleness, and intellect."

One Unitarian clergyman of the North, however, countered that, "The Anglo-Saxon race" was "further advanced in civilization, more enterprising and persevering, with more science and art, with more skill and capital," while southerners/Cavaliers were "poor gentlemen, broken tradesmen, rakes and libertines, footmen, and such others..."

How accurate were such sentiments? In Virginia, indeed, many Royalists who fled the Civil War found refuge with governor William Berkeley in the 1650s. Some of them rose to become great landowners and scions of the Virginia political tradition. The Washingtons, the Madisons, the Marshalls, and so on. But the narrative took a life of its own, particularly as both Southerners and New Englanders found in it a convenient reinforcement of their self-conceptions. Obviously, only a tiny Southern elite could enjoy the privilege, the horseback riding, the card playing and gambling, the rich idleness and absolute power of a true "cavalier". But the story was useful nonetheless as a rallying cry in times of trouble.

To this day, the Cavalier name lives on as the University of Virginia's mascot. James C. Cobb covers the history of this Cavalier cultural identity in his book, Away Down South: A History of Southern Identity.