Why Does the Supreme Court have Nine Justices? Judiciary Acts and "Court-Packing"

Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution establishes a Supreme Court, but it says nothing about the number of judges who should serve on the Court. The current number of nine judges is set not by the Constitution, but by the Judiciary Act of 1869, and there is nothing but precedent and politics to prevent this number from being changed in the future. The relevant text of the Constitution reads simply, "The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish."

Note the lack of any specified number of judges in this text. In fact, one of the most contentious episodes of Franklin Roosevelt's presidency was his attempt to increase the number of judges on the Court from nine to fifteen. This ran into opposition from even his close allies in Congress, and his "court-packing" scheme died in ignominy. Yet there is nothing to prevent this type of measure from arising in the future, but for common reverence of the nine judge precedent.

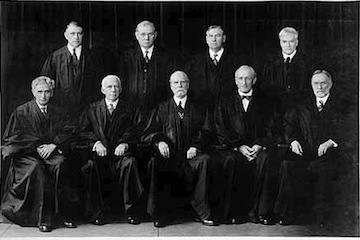

When John Marshall issued his great decisions of the early 19th century, his Court consisted of only six or seven justices. The judiciary of his age was the target of frequent sparring between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, as seen with the Judiciary Act of 1801 (the "Midnight Judges Act" passed under John Adams) and the Judiciary Act of 1802 (passed under Thomas Jefferson). As the nation grew, the size of the Court increased in tandem, until there were ten justices on the Court from 1863-1866. In short order, legislation was passed fixing the size of the Court at seven (1866), and then finally at nine (1869). These acts were as political as Roosevelt's "court-packing" scheme would be 70 years later. When Andrew Johnson was President, in 1866, the motivations of Congress were to deny him the opportunity of selecting new judges. By 1869, Johnson had been replaced with Ulysses Grant, and Congress then saw fit to expand the number of justices.

In the era of the New Deal, Franklin Roosevelt saw several cherished reforms get thrown out by the Supreme Court. The biggest blow came on May 27, 1935. New Deal Democrats came to refer to this as "Black Monday". Three separate decisions were handed down which struck against Roosevelt's power. One (Humphrey's Executor v. United States) declared that Roosevelt could not dismiss regulatory appointees (in this case a member of the Federal Trade Commission) for political reasons alone. Only in the case of crimes or gross neglect could a President do so. Secondly, the Court (Louisville Joint Stock Land Bank v. Radford) determined that a recent law went too far in protecting indebted farmers vs. the contractual rights of creditors to foreclose. And finally, the Court (Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States) invalidated the National Industrial Recovery Act for conferring too many open-ended powers on the Executive branch. This final decision struck Roosevelt the hardest, as the NIRA had been a central piece of the New Deal regulations.

After winning reelection in 1936, Roosevelt attempted to dilute the influence of conservatives on the Court with his "court-packing" bill. The bill would have allowed the President to appoint up to six additional justices, increasing the size of the Court to fifteen. The ostensible purpose was to decrease the workload on judges older than seventy years and six months. A fortunate byproduct would be a Court packed with Roosevelt appointees who would vote in favor of New Deal legislation. The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 was introduced on February 5th. Roosevelt gave a fireside chat on March 9th to argue for the bill. Yet it could never gain the broad support of his other New Deal initiatives. Influential Democrats opposed the bill and held it up in committee. In polls of the American public, a small but intractable majority opposed any attempt to increase the size of the Court. Roosevelt turned to past precedent, pointing out that the size of the Court had been changed several times before, but to no avail. The nation had settled on nine justices as the standard, and the standard seems to have been held sacred by the 1930s and ever since.

What makes earlier Judiciary Acts any different from Roosevelt's bill? Were there not political motivations behind other changes to the size of the Court? It is worth noting that no Constitutional Amendment fixes the number of justices at nine. As the highest court of the land, the Supreme Court necessarily comes under scrutiny and generates controversy with its decisions. It is entirely possible that in the future a President and Congress, acting in sympathy, may attempt to change the complexion of an opposing Court. If history shows us anything, it is that a precedent once deemed sacrosanct can quickly be undermined by the tumult of events. A hundred years from now, will the Supreme Court have nine justices, or some completely different number?