Speculation Gone Awry -- The Kentucky Relief War of the 1820s

Dan Bryan, December 3 2012

An antebellum political speaker makes his case in George Caleb Bingham's painting, Stump Speaking

An antebellum political speaker makes his case in George Caleb Bingham's painting, Stump SpeakingThe battle of creditor and debtor has been present since the first days of the colonies, and the episode that occurred in Kentucky from 1819 to 1825 is particularly illustrative. In that interval Kentucky's political factions established parallel banking systems and courts, grinding the state's business to a standstill over the issue of inflation and debt relief. This battle has been called the "Kentucky Relief War" or the "Old Court - New Court Controversy".

On a human interest level, future luminaries of American politics such as Henry Clay, Francis Preston Blair, and Amos Kendall all played roles as young participants. Blair and Kendall would later be closely aligned with Andrew Jackson while Clay became a staunch opponent.

Land speculating and its fruits in Kentucky

The process repeated itself thousands of times in Kentucky, starting in the 1770s and continuing into the 1800s.

A scrabbler entered a county from the east and used bank loans to gain title to a large amount of land (usually with the help of some political connections). There he sat for a few years (often as an absentee owner), or sometimes less, until the inevitable waves of settlement followed him up.

Via a shrewd distribution and sale of the land, the speculator pocketed his profits and moved west to the next open plot. As the population increased these men took to creating entirely new towns and developing them. With a different backdrop, it's hardly different from the practice of house and condo flipping that survives into the present day.

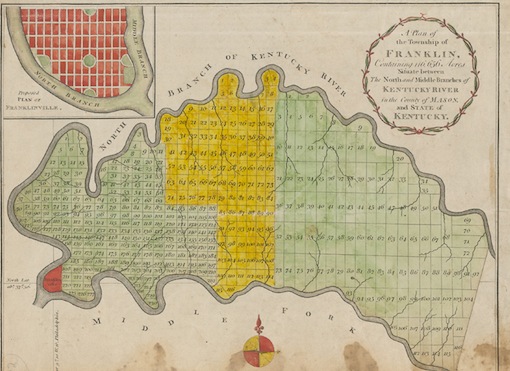

A real estate map of Franklinville, Kentucky -- a town which existed only in the dreams of a land speculator (click for source)

A real estate map of Franklinville, Kentucky -- a town which existed only in the dreams of a land speculator (click for source)This practice lived and died on the availability of credit, which in those days meant the assets of a bank backed by gold or silver. Some banks loaned out a large amount of currency relative to their assets, while others managed their portfolio in a more conservative manner. In Kentucky during the 1810s the economy boomed and the population grew rapidly. State banks (and the Second Bank of the United States after 1817) prospered under loose lending guidelines and the availability of credit was rarely an issue for speculators.

In this environment many were drawn to real estate investing. The profits were high and the work was not as taxing as it was in other professions. A few men could be forgiven for believing they had entered a no-lose situation.

The Panic of 1819 and the real estate collapse

The Panic of 1819 decimated these speculators. As the first bankruptcies and foreclosures came in, the banks in Kentucky belatedly realized they had overextended themselves. As their gold was called back to the east they were unable to write loans commensurate to the needs of the real estate speculators who then withered on the vine, their rage growing hotter by the day. Common farmers found themselves shut off as well and joined the chorus of anger.

The elite of Kentucky society supported the banks. Most of them were creditors and were philosophically amenable to the virtues of a gold standard. Land speculators were usurpers in the eyes of this crowd, and the panic was now giving them their just comeuppance. Many of these elite were planters who owned slaves and had established plantations. They had invested in the banks in many cases and stood to lose greatly from any sort of debt forgiveness or inflation.

The speculators and indebted farmers of the state formed the Relief Party to press their claims. Above all they wanted inflation. They elected majorities to the state legislature in the 1820 elections who promised to fulfill these goals.

Conservatives in Kentucky and elsewhere looked upon these developments aghast. Kentucky had been among the first states to remove property qualifications as a criteria for voting, and now it seemed to those outside the fray like a rabble had seized control of an entire state government.

The Relief Party in control, and the fracturing of Kentucky's banks and courts

The Relief Party wasted little time in enacting their agenda. By the end of 1820 an experiment in loose banking was established, virtually guaranteeing a wave of inflation. The legislature also suspended collections on any loans for the period of one year. Outrage ensued from the creditor class.

The legislature created inflation via a new Bank of the Commonwealth, designed to be extremely debtor friendly. This new bank had no specie behind its notes, but creditors were required to accept them by state law. In practice this established a fiat money system in the state, which was extremely radical for those times.

With the legislature lost to them, creditors challenged these laws in the state courts. Here they won victories and by 1823 were able to strike down the suspension of collections. Bankruptcies, foreclosures, and payments from debtor to creditor continued apace.

Not giving up, the Relief Party simply established a new state court. Competing decisions were handed down, the old courts refused to dissolve, and an extraordinary situation came into being whereby two separate courts claimed to have the highest authority in Kentucky. These became referred to, simply enough, as the Old Court and the New Court. Observers feared a civil war would erupt within the state if passions continued to remain inflamed.

Henry Clay, Francis P. Blair, and Amos Kendall

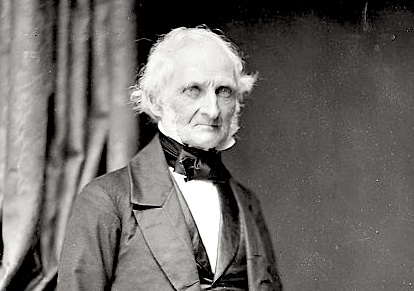

Amos Kendall and Francis Preston Blair were two figures in the center of this controversy on the side of the Relief Party. Blair was one of the judges on the new court, and Kendall was a publisher who became famous in his defense of the system. Both of these men became key allies of Andrew Jackson and later formed part of his so-called "Kitchen Cabinet" when he was President.

A portrait of Amos Kendall, late in his life.

A portrait of Amos Kendall, late in his life.Henry Clay, on the other hand, was the most prominent opponent of the scheme. He supported a strong, national financial system backed by the Second Bank of the United States, and he was appalled at Kentucky's willingness to strike out from this situation.

The Relief Party succeeded in their goal of initiating a round of inflation. This may have been good in the short-term for those who were indebted, but it caused great instability in prices and land values and did not help to grow the larger economy. Eventually a backlash developed against the scheme and by the mid-1820s the Relief Party fell out of favor.

Henry Clay's reputation was enhanced. By combining his defense of nationalism and of conservative financial practices, he burnished his credentials with the Democratic-Republicans (later the Whigs) and ran for President several times. As a candidate in 1824 he carried the state of Kentucky and then assisted in the election of John Quincy Adams.

A younger Henry Clay, around the time of the Kentucky Relief Wars

A younger Henry Clay, around the time of the Kentucky Relief WarsEventually the economy of Kentucky picked up again, gaining momentum from the national recovery, and the issue of the New Court vs. the Old Court receded from prominence. In 1826 the New Court was rescinded and the judicial branch of Kentucky was reunited. Thus was demonstrated the other eternal truth -- that the only lasting remedy for a financial crisis is a renewal in growth generating new, performing loans for the banks.

Hard times, debt relief, and inflation

The demand for inflation and debt relief has always been present during rough economic times (be it the 1780s, 1819, the 1890s, or the 1930s), and it no doubt will reemerge at some time in the future. Perhaps the issue will be student loans, state and local pensions, or even the federal debt itself. Perhaps it will be something else that's not yet apparent.

Whatever the cause, anyone who is tempted to believe that the real estate crisis of 2008 was an anomaly, or that better regulation will prevent it in the future would do well to look upon the history of finance in the United States. It is littered with the tales of panic and collapse, such as that in Kentucky and elsewhere that occurred in 1819, and the aftermath of such events is always devastating for the unprepared.

The best an individual can do is to remain vigilant on behalf of their own interests, for surprise is the most dangerous adversary of all.

Recommendations/Sources

- Wilma A. Dunaway - Speculators and Settler Capitalists: Unthinking the Mythology about Appalachian Landholding, 1790-1860 (in Appalachia in the Making: The Mountain South in the Nineteenth Century)

- Bank of Kentucky and Bank of the Commonwealth

- Class Rivalries in Frontier Kentucky and the Applicability of Jeffersonian Agrarianism

- Murder and Inflation in Kentucky

- Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. - The Age of Jackson (Back Bay Books (Series))

- David S. Reynolds - Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson (American History)