The Gay Bars and Vice Squads of 1950's Los Angeles

Dan Bryan, January 7 2013

In the wake of World War II a conformist impulse reasserted itself in American society. At the same time thousands of gay men found themselves in California after World War II, and they were presented with the problem of living a life in the midst of social disapproval and police repression.

In Los Angeles throughout the 1950s, the culture of gay men functioned very much below the radar. Under constant harassment by the police, homosexuals risked social ostracism and loss of employment if outed.

Homosexuality as a disease

The dominant perception of homosexuality in the 1950s was that it was a disease. The psychiatric community was nearly unanimous in this assessment and others took their cue from this stance. Most employers and government agencies barred homosexuals with morality clauses and they were widely considered to be security risks. In daily language they were often defined as "deviants", "perverts", or "inverts", when they were not being painted as pedophiles.

Psychiatric opinions

In 1952 the American Psychiatric Association published the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders for the first time. It included homosexuality as a mental disease.

This was a predominant view in the mental health profession for the entire decade (an important exception was Evelyn Hooker). It was widely conjectured that homosexuality resulted from emotional traumas in childhood, as is the case with other mental illnesses, and that genetics played little to no role. On this basis the practice of conversion therapy took hold, with widespread attempts to change people from homosexual to heterosexual (here are just a few examples from students at Oberlin College in Ohio).

Employment restrictions

It was common practice for employers to prohibit homosexuality. Homosexuals had long been barred from employment in federal jobs, a policy that was reinforced in 1953 by Dwight Eisenhower's Executive Order 10450. Private employers varied on this issue, but most would fire any employee who was discovered to be gay. Thus at a very basic level, to identify oneself as a homosexual in public was to invite a lifetime of poverty.

Social mores

The disapprobation of psychiatrists and employers reflected the overt hostility of the mainstream American mindset. An unfortunate tendency was for many people to conflate homosexuals with pedophiles and serial killers. Public safety videos of the time made this connection explicit and helped to spread much fear and misinformation.

A survey conducted as late as 1967 for a CBS documentary (see the full program or a shorter version) determined that two thirds of Americans viewed homosexuals with "disgust, discomfort, or fear" while a majority favored laws against all homosexual acts.

Sodomy was illegal in every state until Illinois decriminalized it in 1961, and the laws on this were well enforced in the 1950s. Campaigns in Sioux City, Iowa and Boise, Idaho resulted in multiple arrests and involuntary confinements. There were very few voices that dissented from this policy.

The rise of the gay bar in L.A.

Due to an important court case in 1951, California became the first state where gay bars could legally operate. Although the patrons were frequent targets of police harassment, Los Angeles had a decent number of such establishments by the mid-1950s. This corresponded with the first, halting steps towards creating advocacy organizations for gay rights.

Stoumen v. Reilly

In 1951 the California Supreme Court ruled that a bar could not lose its liquor license because it catered to gay clientele. The case was Stoumen v. Reilly.

While this did little to advance the public acceptance of homosexuality, it did allow gay bars to operate in much of California. While a number of these bars were established in Los Angeles by the 1930s, a new wave joined the fray in the wake of this decision (It should be noted that many were closed in spite of this court ruling in a mid-1950s wave of enforcement).

The Los Angeles gay bars

Some of the well-known gay bars of this time were the House of Ivy and the Windup in Hollywood, and the Crown Jewel, Harold's, the Waldorf, and Maxwell's in downtown Los Angeles.

Many of the gay bars in Los Angeles were located near Pershing Square, which was a cruising ground in its own right

Many of the gay bars in Los Angeles were located near Pershing Square, which was a cruising ground in its own rightThe character of these places varied widely, reflecting divisions within the gay community. The Crown Jewel was known as a rather straight-laced bar, with a dress code and many patrons who wished to remain discreet. Maxwell's operated on a different end of the spectrum, with a much more flamboyant crowd.

The more conservative group of the gay community took pains to distance themselves from the "obvious" crowd, believing that they perpetuated negative stereotypes and drew unwanted attention. Helen Branson, who operated the Windup, wrote:

"I have not touched on the problem of the obvious homosexual. He is in the minority. I think he brings the censure of the public not only on himself, but is the main cause of all averse judgment against the group as a whole.... I do not welcome this type in the bar. I am rude to them, watch them closely for any infraction of my arbitrary rules, and they soon leave."

Other recreation: bathhouses, parks, and parties

Bars were not the only place where gay men congregated in this time period. There were bathhouses and parks that were known to be more homosexual, and small groups held house parties and private engagements. None of these places were particularly more safe than the others in regards to police harassment. Even a private home party could be the target of a sting operation and as such, invitations to them were very few. It was thus quite difficult for individual gay men to coalesce into a broader community.

The homophile movement and the Mattachine Society

The creation of the first gay bars in L.A. corresponded with the rise of a group called the Mattachine Society.

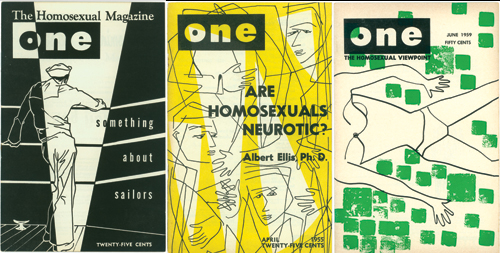

The Mattachine Society was an organization founded in 1950 to advocate for the cause of gay rights. For at least a few years it was the only group of its kind in the United States. The initial founders were radical Communists, but the organization was taken over after a couple of years by more mainstream activists. It was in this time that the term "homophile" was coined -- explicitly to take the word "sexual" out of homosexual.

This terminology placed the Mattachines at the more accommodating end of the gay spectrum, vis a vis the "obvious" homosexual. Divisions within the community would eventually come to a head in the late 1960s, and the homophile label fell by the wayside as the gay community asserted itself more forcefully.

The LAPD Vice Squad

The Los Angeles Police combatted the homosexual scourge with a notoriously vigorous Vice Squad. Using a large number of undercover officers who posed as gay man for purposes of entrapment, the Vice Squad harassed the gay community in L.A. for decades.

The entrapment process

It is said that the LAPD recruited heavily from that set of men who had failed to obtain acting roles in Hollywood. Often young and athletic, these men were trained to impersonate the gay mannerisms and language of the time, and were sent around to different bars. Often they had quotas for the number of "perverts" they were expected to bring in for a given week or month.

Helen Branson described it as such:

"They offer someone a ride or accept a ride and that does it. Some of them play fair, inasmuch as they wait for the gay one to make a pass at them, but many others wait only long enough to get in the car before declaring the arrest. The officer's word, of course, will be taken as true, and they always count on the victim not wanting publicity. They know he will pay the fine and be quiet. The fines for this charge amount to a considerable sum in a year's time."

The results of entrapment

One the first successful defenses against this tactic came in 1952, when Dale Jennings of the Mattachine Society took his case to court. Jennings declared himself to be a homosexual, but asserted that the charges against him were manufactured. The charges were dropped after the jury deadlocked.

Most gay men did not realistically have the option of going to court if they could avoid it. Defending the charges in these stings would have nearly always led to loss of employment, and potentially other scandals. The most common outcome was to make a plea bargain for a lesser charge in the hopes of paying a fine. In this manner, the Vice Squad harassment became a recurring shakedown of the gay community, and it continued until well after the 1950s.

Many of those who were convicted of crimes became registered sex offenders. Many lost their jobs or otherwise had their lives ruined. Such was the price of being a gay man in the 1950s.

Recommendations/Sources

- Edward Sagarin - The Homosexual in America

- Gay Los Angeles

- Daniel Hurewitz - Bohemian Los Angeles: and the Making of Modern Politics

- Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons - Gay L. A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, And Lipstick Lesbians