Prelude to a Riot -- Irish Athletic Clubs and the Black Belt in 1919

Dan Bryan, May 20 2012

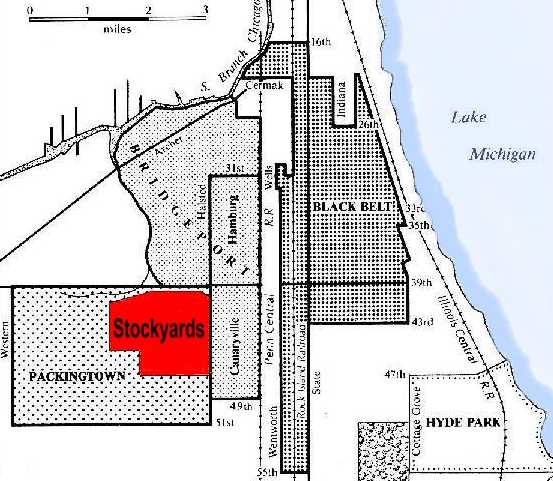

The Neighborhoods of the South Side in 1919

The Neighborhoods of the South Side in 1919The Chicago Riots of 1919 were one of the biggest instances of unrest in that city's history. They did not appear from thin air. Behind the surface of that violence was a rabbit hole of resentment and recrimination between the city's Irish and black communities, stretching back for years.

The two groups had fought for jobs, neighborhoods, and political power in a within a narrow section of the city's streets. In the months before things finally exploded, there was an ample string of incidents that made the atmosphere intolerably tense. These included layoffs, the enforcement of a "color line" at Wentworth Avenue, home bombings, and simple electoral politics.

Ragen's Colts -- The Irish South Side and the athletic clubs

The Irish community in Chicago was centered in the South Side, to the north and east of the stockyards. Their neighborhoods were Bridgeport and Canaryville. The Irish had lived in these neighborhoods for decades, since the great waves of immigration started in the 1800s.

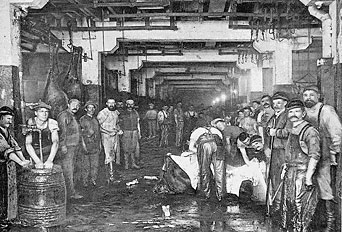

In Chicago the Irish were a powerful group with a substantial amount of political influence. The police department was stacked with their ranks, and many worked in the packing yards as well. For many years, they had tried and failed to monopolize the packing house work to their own group, and they lived on uneasy terms with the Poles, Lithuanians, and other immigrants who competed with them for work.

One feature of the Irish neighborhoods was the ubiquitous presence of athletic clubs. For young boys on the make, these places were the first step in gaining respect. These groups of teenagers and young men drank, threw parties, chased girls, fought each other, assaulted any outsiders who wandered into their neighborhoods, and between all of that, they played a little baseball.

Many of the clubs were informally tied to prominent Irish politicians. One of the more infamous groups, Ragen's Colts worked under the auspices of Frank Ragen, who served at varying times as an Alderman and Police Commissioner. During election season they raised funds, mobilized the vote, and intimidated election officials into giving favorable counts.

Boys who proved themselves in these clubs were marked for political advancement as adults. For instance, Richard J. Daley was elected president of the Hamburg Athletic Club when he was twenty-two, and he used that as a springboard to his other political offices.

Due to their young age, violent nature, and self-perceived status as defenders of the Irish hood, these athletic clubs came to play a central role in the rioting.

The Black Belt and the Great Migration

The black community was a new thing in the Chicago of 1919. While a few had always lived in the area, the first wave of the Great Migration only happened during the Great War. Between 1916 and 1918, about 50,000 blacks escaped from the South in search of employment and human dignity. In many cases the word "escape" can be taken literally. Most were heavily indebted sharecroppers who were forced to sneak away in the middle of the night to avoid arrest or worse. They arrived in Chicago with nothing.

They lived in a narrow stretch of real estate down the center of the South Side, in what was known as the Black Belt. As they grew in numbers, their housing situation became increasingly overcrowded. To the west, Irish gangs enforced Wentworth Avenue as Chicago's "color line", while to the east they were hemmed in by Lake Michigan. Rent was expensive for the quality of the housing.

At times, the new arrivals mixed uneasily with the established black community. The established Chicago community was more prosperous, middle-class, and educated. The new arrivals from the South shared none of those traits. Some of the older residents complained that the new migrants "brought discrimination with them" as their visibility increased, and as they came to be perceived by whites as competitors in the cutthroat job markets.

Competition for jobs in the Chicago stockyards was intense

Competition for jobs in the Chicago stockyards was intenseA primary means of employment were the stockyards on the southwest side. Others worked in the numerous steel and machinery shops. They were far more likely to be non-union, and many worked for lower wages than the other employees. As such they were despised by the union members. Historically they had been hired as strikebreakers -- in 1904 at the stockyards, and in 1905 as teamsters for instance, and more recently in myriad smaller industries. Through these incidents, the words "Negro" and "scab" became synonymous in many Chicago neighborhoods.

Black workers didn't want to unionize in large part because their jobs were the most tenuous. When layoffs came in 1919, they fell disproportionately on the black community. By the end of the spring about 20% of them were unemployed in Chicago, and the rest feared that number would be higher if they expressed sympathy for the labor unions.

At the same time, companies like Armour, Swift, and Sears treated their black workers better than they had been treated by the unions or by any other group of white men in their life. These companies also financed black organizations and charities, which influenced the prominent citizens of that community to form a favorable impression. In the meantime, the unions vacillated between half-hearted overtures and racial exclusion and violence.

Incidents of 1919 before the riots

1919 was not a good year for the overall social health of America or Chicago. With the end of the Great War and its demobilization, 2.5 million veterans were discharged within a six month period. Unemployment, labor strife, and fears of radicalism became part of the landscape.

In Chicago, the economic issues played out in the stockyards. To get to their jobs, thousands of blacks had to commute across the Irish neighborhoods, and were subject to assault and intimidation in transit. Where there had been a labor shortage just a couple years previously, there were now layoffs and this made the different groups of Chicago very uneasy with each other. A huge strike was being planned behind the scenes at the stockyards, and most other groups feared that the blacks would undermine it by refusing to participate.

Additionally, the mayoral election of 1919 had returned a narrow victory for the Republican -- William Hale Thompson. The margin of 21,000 votes was dwarfed by the number of new arrivals from the South. To the Irish Democrats, this was yet another source of their resentments.

A vandalized home in 1919. A number of black-owned homes were bombed in the months before the riot.

A vandalized home in 1919. A number of black-owned homes were bombed in the months before the riot.For their part, the black community had been victim to numerous home bombings. Starting in 1917, any home occupied by blacks that was near the edge of the neighborhood, or across the "color line", was at high risk of being firebombed. Twenty-five homes were bombed in the year preceding the riot, and a six year old girl was killed early in 1919. The police were not helpful in prosecuting these cases.

Then on June 21, an incident occurred that drove home to the black community how little protection they had from the police. Two unarmed black men were attacked and killed by Irish hoods (likely from Ragen's Colts) on no pretext whatsoever, with witnesses, and the police refused to make any arrests whatsoever. Rumors and outrage spread almost instantly.

By now the Black Belt contained thousands of World War I veterans who had expected better upon their return than unemployment and racial violence. The "New Negro", as he was called, was appalled by the negligence of the system. More importantly, he was prepared to do something about it. The Chicago Defender and The Whip had given up on the police, and began to advocate militant self-defense by the summer of 1919.

"The Whip informs you, the whites, that the compromising peace-at-any-price Negro is rapidly passing into the scrap heap of yesterday and being supplanted by a fearless, intelligent Negro who recognizes no compromise but who demands absolute justice and fair play."

In the weeks after this incident, there was talk on both sides of confrontations and trouble, and a general edge to the ambience. The peril of rioting was ready to strike at any moment. Only the ultimate catalyst was in doubt.

*See Also: The Chicago Riots of 1919*

Recommendations/Sources

- William M. Tuttle, Jr. - Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919

- The 1922 Report by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations