Are the Causes of Shays' Rebellion Fairly Portrayed?

Dan Bryan, June 14 2012

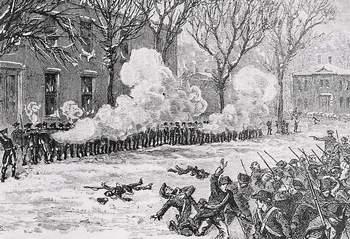

One of the last important events under the Articles of Confederation, Shays' Rebellion is usually presented as the final evidence of that system's failure. Across Massachusetts, hundreds of men shut down courts, marched in military discipline, and even attempted to take over an armory in Springfield. They were only stopped by a full mobilization of the Massachusetts Militia.

Many of the men were veterans of the Revolution, and their actions shocked most of America's political class. They were even deemed serious enough for George Washington to bring a premature end to his retirement and attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

And what were the actual causes of their resentment? Were they reasonable or outlandish? Was this rebellion any more radical or extreme than the American Revolution had been in 1775? These questions were strategically ignored by America's political elite as they met to create a stronger national government.

Most Revolutionary War Veterans Were Owed Money

The finances of the Continental Congress had been so tenuous that they could barely pay themselves. By the end of the Revolutionary War, many soldiers had not been paid in years. Instead they were presented with bonds, promising future redemption. Individual states, including Massachusetts, duplicated this practice for their regiments.

As time went on, most of these bonds were not redeemed. Those soldiers who hadn't sold them to speculators -- for pennies on the dollar -- were left holding them in frustration. Only a few states had managed to make significant payments, and the national debt had barely been dented.

Wooden engraving of Daniel Shays and Job Shattuck, leaders of the rebellion.

Wooden engraving of Daniel Shays and Job Shattuck, leaders of the rebellion.At the same time, many merchants and businessmen who had played a much smaller role in the struggle seemed to be relatively prosperous in the 1780s. It sowed much ill will for the new Confederation that in so many states, those had sacrificed the most for the American Revolution had the least to show for it.

Farmers Were Poorly Represented in Government

The state government of Massachusetts was dominated by coastal merchants. For many decades they had been the most prominent and prosperous citizens, giving cities like Boston their importance and providing the economic base of the region.

Naturally, the political system was set up to ensure their dominance. The farmers in other parts of the state did not send enough representatives to state government to effectively promote their agenda. In addition, minimum property and wealth requirements for voting and holding office disfranchised many of them.

Taxes Were Disproportionately High

Times were hard in first years of independence. For the merchants of New England their former trading partner, Great Britain, was now hostile. Consequently, overseas businesses now required payment in gold and did not extend credit. This credit crunch worked its way through the rest of the Massachusetts economy.

In the realm of business, merchants demanded payment in gold from farmers and small businessmen elsewhere in the state. Since most farmers were of modest means, and usually in debt themselves, they rarely had gold on hand.

In the realm of taxes, the state began to require payment in hard currency as well. The change was particularly pronounced when John Hancock was replaced as Governor by James Bowdoin, who was the favored candidate of the Massachusetts elite. He supported their attempts to recover debt and taxes only in the form of gold. John Hancock, on the other hand, had allowed payment with paper currency as well.

In addition to taxes on property, there were acrimonious disputes over taxes in place to support the Congregational Church.

The itinerant tax collectors were despised in much of the state. Their presence would be one of the biggest causes of Shays' Rebellion.

Farm and Property Was Being Confiscated

What happened to those who couldn't afford to pay their debts in gold? For those unfortunates -- a majority in many locales -- lawsuits and judgments awaited in county court.

Daniel Shays' Farmhouse in Pelham, MA.

Daniel Shays' Farmhouse in Pelham, MA.Against the state, their cases were hopeless. Not only were the judges hopelessly indifferent to the plight of the farmers, but the letter of the law was against them as well. After all, did they not owe a certain amount in taxes each year? Even if those taxes had been sharply increased in ways that ensured farmers would pay more than their share?

Against private merchants, the outcomes were much the same.

When farmers couldn't afford to pay the judgments rendered against them, their possessions were auctioned off to make up the difference. In many cases this involved selling the farm itself, or at the very least livestock and other essential possessions. Since the area was depressed and specie scarce, the prices at these auctions were very depressed. Few farmers felt like they received fair value for the property they lost, and on top of that it went mainly to the same coastal elite that they already so despised.

Daniel Shays himself had been presented with an honorary sword by Marquis de Lafayette during the Revolutionary War. In the 1780s depression he was forced to sell it for a few dollars to help repay some of his debts. He had been summoned to court on other occasions as well, like many men of his cohort.

Debtors Were Being Imprisoned

Debtors' prisons were commonplace in 1700s America, and in Massachusetts. They were generally not used as a criminal penalty, but rather as a means of securing judgment in a civil case. Creditors had the right to have a man imprisoned for debt on the assumption that well-heeled family or friends would emerge to make good on the obligation.

Terms of imprisonment were usually short, and security minimal. Delinquents were expected to spend their nights in jail, but during the day were released into town to work. There was enough surveillance in most towns to prevent an escape, and most men either repaid their debt or were released on oath (of future payment) within a few months.

This is mentioned only to correct some impressions that most people no doubt have of such prisons. In practice however, being sentenced to one was a humiliating experience, and the entire legal process was seen as favoring creditors and lawyers, always at the expense of the common man. For many people who had been indebted and summoned to court through a system rigged against their interests, imprisonment for any amount of time was the final straw.

When the resentments boiled over in Shays' Rebellion, the first targets were the county courts. In several locations, mobs surrounded the courthouses and prevented any legal business from proceeding. It was only after this was accomplished that the men's attention could be focused towards any other target.

The Legacy of Daniel Shays and Shays' Rebellion

Given all of these facts, is there any wonder that the farmers and debtors of Massachusetts rebelled? That there was rebellion when so many were owed money by Massachusetts and by the Confederation, and at the same time being prosecuted for failure to pay their own debts? Was it not a bit ironic that they rebelled against some of the same men who had so recently rebelled against Great Britain? That some of these same men called the Shaysites a rabble and a mob?

Opinions were divergent. Shays' Rebellion was the episode that compelled George Washington out of retirement, in fear that the country would plunge into anarchy. James Madison and Alexander Hamilton agreed and used it to bolster support for their Constitutional Convention. Sam Adams was a merchant from Boston and in direct opposition to the farmers, while John Hancock was their fervent political advocate.

Thomas Jefferson, viewing the situation from France, was delighted to see the Massachusetts aristocracy challenged so brazenly. The rebellion gave rise to one of his most famous quotes:

"God forbid we should ever be 20 years without such a rebellion... The tree of liberty must be refreshed with the blood of patriots & tyrants."

Yet over time, Jefferson's view has not prevailed. Since Shays' Rebellion led so directly to the Constitution, there has been a tendency from all quarters to put it down to impudence and ignorance. In general, Shays has survived in the history books as something of a villain or a rabble-rouser, even if there wasn't much he did that the Founders of the United States hadn't done ten years earlier.

Recommendations/Sources

- Leonard L. Richards - Shays's Rebellion: The American Revolution's Final Battle