The 1933 Banking Crisis -- from Detroit's Collapse to Roosevelt's Bank Holiday

Dan Bryan, September 30 2012

Depositors outside of Guardian National in Michigan, 1933

Depositors outside of Guardian National in Michigan, 1933The deepest banking crisis of the Great Depression was touched off by the pending failure of two Detroit banks in early 1933. For several weeks, by law, every bank in the entire state of Michigan was closed for business. It was from these beginnings that a national banking crisis engulfed the final days of the Hoover Administration. What transpired to bring on such a calamitous event? How did individuals cope in that interval without a banking system?

Instability in the Michigan banking system

Even in the 1920s, banking failures had dotted the rural landscape of the country as the new wave of industry and commerce constricted the traditional lifeblood of agriculture. 1929 saw the great stock crash, and 1930 brought with it a new tariff and onerous tightening from the Federal Reserve. In 1925 there were 617 banks that failed in the United States. In 1930 that number was 1,350 and by 1931 it was 2,293. With each failure came an obliteration of many people's life savings, and fear began to spread through the country that an unstoppable cascade would soon materialize.

It's hard to say why the final panic was specifically precipitated in Detroit, as opposed to any other benighted part of the nation (there is always a semblance of chance in human affairs). But it was in February of 1933 that the banking system was frozen in the entire state of Michigan, precipitating a national crisis.

Trouble at Ford Motors

Sales of the Ford automobile collapsed after 1929, and with them did collapse the fortunes of Detroit. At great risk to his own assets and contrary to many businessmen of the time, Henry Ford pressed on. His company continued to work on the development of the Model B including an early variant containing the flathead V-8 engine. The first of these cars rolled off the line in 1932, a year in which Ford lost $75 million.

Unfazed in public, Ford said, "We didn't lose it -- we used it. If we had dropped it on the stock market, that would have been losing it."

Such statements were of little help to the stability of Detroit's financial institutions, whose success was greatly intertwined with Ford's. At the start of 1933, Detroit's banks were losing between $2.5 million and $3 million a week in deposits. The two largest banks, the First National Bank of Detroit and the Guardian National Bank of Commerce, were teetering on the precipice of insolvency.

Detroit's unemployed and indigent

The situation within Detroit proper at this time could hardly be described as tranquil. There were about 400,000 unemployed in the city, many of them laid off from the auto industry, and they began to form Unemployment Councils for support. These Councils demonstrated against evictions and tried to raise money for the unemployed, but with up to 80% of the city's auto manufacturing capacity laying idle, the size of the challenge was insurmountable. There was no welfare, no unemployment insurance, no Social Security, and no deposit insurance to protect the meager savings of these workers against the cascading bank crisis.

The early 1930s in Detroit saw clothing drives, thrift gardens, reductions in rent, and the donation of crops from charitable organizations. Prosperous citizens contributed thousands and even hundreds of thousands of dollars to the relief efforts. The city and the state were unable to add much to this total. Tax revenue was meager and there was no assistance from the federal government for relief programs. Many families who lost their homes ended up living in the open air of Clark Park where charity provided them to the best of its ability.

Radical leaders gain support

Communist movements gained strength.

On March 7, 1932 a procession of marchers was organized in Detroit and directed towards the Ford plant in Dearborn. Their goal was to present a list of demands to Henry Ford for a shorter workday, increased employment, health care, and union recognition. While deprivation knew no bounds politically, this particular march (the Ford Hunger March) was organized by William Z. Foster and Albert Goetz, the most important Communist leaders of the Detroit area (Foster would go on to win 103,307 votes in the 1932 Presidential Election and later died in the Soviet Union).

Unemployment Councils joined the march. No sooner did the group cross into Dearborn than they were showered with tear gas and pelted with bullets. The Dearborn Police Department joined with Ford's own Service Department to chase the marchers back. Five of the protestors were killed by the bullets -- all of them members of Communist organizations.

One week later, a much larger march took place in Detroit to protest the shootings. 60,000 people sang the socialist anthem "L'Internationale" as they proceeded through the streets. However cathartic this was for its participants, as a practical matter it solved nothing. Detroit continued to suffer the worst effects of the Depression, and the streets and parks continued to overflow with the starving and the homeless.

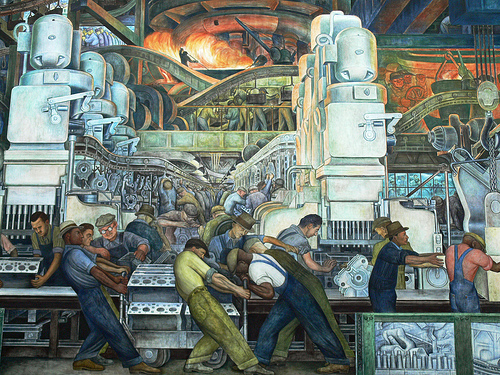

Diego Rivera's murals -- a record of the times

The Mexican painter Diego Rivera left a lasting monument to this time period with his artistic work. In April 1932 he arrived in Detroit with Frida Kahlo and both of them produced much work there over the course of their stay. Rivera was commissioned to produce murals of Ford's factory for the Detroit Institute of Art. The unveiling of these murals enraged some Detroiters and inspired others.

The two mixed uneasily amongst the high society of Detroit. Kahlo especially disliked the city ("Mr. Ford, are you Jewish?" she asked at a social function), but when the two left for New York in 1933, they possessed a check for the princely sum of $25,000. The commissioner of the murals? Edsel Ford.

The Michigan Bank Holiday

By February 1933, First National and Guardian National were on the verge of death. Through their official channels, they reached out for a loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, a newly created initiative by Herbert Hoover to provide financing and support to struggling American businesses. The Secretary of Commerce, Roy D. Chapin (himself an auto man from Michigan), was dispatched to Detroit to ascertain the situation and to make a decision.

Chapin approached Henry Ford, the largest depositor in these banks, and asked if he might be able to accept some level of refinancing. Ford had already done this on previous occasions, and his own company was coming off of the huge financial losses of 1932 mentioned above. He explained that he was unable to provide further assistance, even after much pleading and negotiating from Mr. Chapin and from banking leaders. He also asserted that should the banks continue to waver, he would be forced to withdraw Ford's assets from them. By February 13 it was clear that Mr. Ford's mind could not be changed. Furthermore there was an imminent threat of Ford triggering the collapse of these two banks himself (to save his own assets) upon resumption of business the next day, after a long weekend.

Thus on February 14 at 1:32 in the morning a general banking holiday was declared in Michigan by Governor William Comstock. The prompt action was in direct response to the threats of Henry Ford. Across the state of Michigan people woke up on that Tuesday morning to the knowledge that they would be able to withdraw no cash from their accounts for the next eight days. Governor Comstock himself had a total of $30 on his person (with creditors chasing thousands) when presented with the need for emergency action, and simply remarked, "I'll get along."

The spread of the banking crisis

The bank holiday did not end after eight days, and it did not stop in Michigan. The first order of business was for the state's newspapers to explain the order in a calm, supportive manner to prevent a general panic. "Sit tight, all is well." said the Grand Rapids Herald.

Between the lines, it was understood that the trouble emanated from Detroit. Many banks made exceptions allowing depositors to withdraw small sums for daily use. After three years of calamity a certain majority was inured to financial crises and simply continued business as best they could, for what other option was there? At least the chances of another bank run were removed for the next two weeks. Was that not a holiday in the truest sense of the word?

On a national level, other papers implored their readers not to take the case of Michigan too seriously. The New York Herald Tribune stated, "... it is well to bear in mind that the banking situation in Detroit is by no means typical of that of the United States as a whole." and continued with a litany of how Detroit's troubles were especially severe.

Unfortunately these words proved to be far from prophetic. By the time that Roosevelt was inaugurated, 37 states had suspended their banking operations. In each case there was a growing sense of dread that the national system was dying -- that the economic calamity of 1929-1933 was but a precursor to even darker times ahead. In many towns, the economy functioned on "scrip" or outright barter.

Roosevelt declares a federal bank holiday upon his inauguration

In the annals of awkward dinner engagements, the traditional pre-inaugural dinner between Hoover and Roosevelt must surely compete for some kind of prize. Hoover was furious because he felt that Roosevelt had undermined him during the final weeks of his administration, as the nation collapsed, by refusing to cooperate on any emergency measures.

Roosevelt for his part did ignore Hoover's pleas. Roosevelt was not opposed to any emergency actions that would end at the moment of his own inauguration. However, he would not agree to any longer-term policies (or make public statements in favor of the gold standard) for fear of reducing his own flexibility upon assuming office. The more cynical have charged that Roosevelt wished to assume office at Hoover's lowest point, so that he could take an enlarged share of the credit for his own remedies.

In any case, the two men and their confidants dined in icy silence on March 3, 1933 as the country lie in shambles. Two days later, Roosevelt declared a federal banking holiday. Within a week he had pushed the drastic Emergency Banking Act through Congress to provide some semblance of stability. His first Fireside Chat was dedicated to explaining these measures, and most Americans approved heartily.

The Detroit financial system is reformed and the banks reopen

In this long interval, the banking system in Detroit was reorganized. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation worked with Alfred Sloan, president of General Motors, to create the National Bank of Detroit. This bank received federal funding and assumed the assets of the two failing banks -- First National Bank of Detroit and the Guardian National Bank of Commerce. Sloan committed a substantial amount of G.M. capital to the new institution while Henry Ford continued to remain on the sidelines. This perhaps ensured that the phrase, "What's good for Ford is good for America." would never enter the national lexicon.

The doors finally opened on March 24, 1933 -- 36 days after the 8 day holiday was first declared. There was an immediate rush of customers, but this time it was to put their money in to the new bank. The larger issue of the Depression remained piteously unresolved, but the single most acute phase of the crisis had passed. Their banking system stabilized, the people of Michigan looked to see what Roosevelt would do next.

Recommendations/Sources

- Francis G. Awalt - Recollections of the Banking Crisis in 1933

- How the Depression Changed Detroit

- Number of failed banks by year: 1921-1933

- Frederick Lewis Allen - Since Yesterday: The 1930's in America, September 3, 1929 to September 3, 1939

- Adam Cohen - Nothing to Fear: FDR's Inner Circle and the Hundred Days That Created ModernAmerica